When World War II broke out, the British government was led by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Within a year, Chamberlain would be replaced, becoming little more than a footnote in the history of the war. He was completely eclipsed by the man who followed him – Winston Churchill.

How did Churchill come to replace Chamberlain in a nation already struggling with the crisis of war?

Churchill’s Background

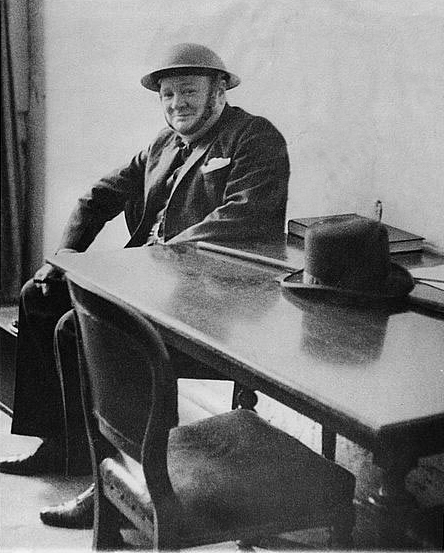

Winston Churchill was a veteran politician and one of the most characterful figures in British politics. Born into an aristocratic family in 1874, he served in the Army before being elected as a Member of Parliament for the first time in 1900.

During a long political career, he switched from the Conservative Party to the Liberals and then back again, holding cabinet positions as a member of each party.

In the 1930s, Churchill was outspoken in drawing attention to the Nazi threat and calling for rearmament, in contrast with the government’s policy of appeasement.

Having spent time outside of government, he was brought back into the cabinet at the start of WWII, taking up a post he had held during World War I – First Lord of the Admiralty.

Chamberlain’s Failure

While the outbreak of war vindicated Churchill, it completely undermined Chamberlain. His policy of appeasement, letting Germany swallow neighboring territory to keep the peace, was shown to be a failure. His unwillingness to confront Hitler had left Great Britain ill-prepared for war.

This became startlingly clear in April 1940, when Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. Great Britain and France rushed to help the Norwegians, but it was too little, too late. Within a month, the Germans were storming through the country, driving the Allies before them.

A crisis had come to Europe and Chamberlain’s government was failing to tackle it.

The Norway Debate

In Parliament, the opposition demanded a debate on the disastrous Norway campaign. On the 7th of May, they got their way.

Though theoretically about Norway, the debate was really a wider one, addressing Chamberlain’s competence to lead the country. Leo Amery quoted from a speech by Oliver Cromwell when he said to the Prime Minister “In the name of God, go!”

Amery’s rhetoric matched the mood of Parliament. Chamberlain was viewed poorly not only by the opposition Liberal and Labour Parties but also by many of his fellow Conservatives.

Churchill’s Stand

Given his views prior to the war, it would have been natural for Churchill to fall in line with the opposition. When he rose to give the final speech of the two-day debate, he did so in front of an angry and expectant chamber.

Churchill had been one of the few men to strongly oppose Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement. As First Lord of the Admiralty, he had joined with him in organizing the Norwegian campaign.

He felt that he had earned the right to criticize Chamberlain’s performance, but that the opposition had not.

In a strongly worded speech, Churchill defended the government’s performance in Norway and lashed out at the opposition. It was not a performance judged to make him friends.

Following Churchill’s speech, Parliament voted on what was effectively a motion of censure against the government. 30 Conservatives voted with the opposition and 60 abstained. The government lost.

Chamberlain Seeks Change

The next day, the 9th of May, Chamberlain summoned a handful of the most powerful men in Great Britain. From his own party came Churchill and Lord Halifax. From the Labour party, the largest block in opposition, came the leader Clement Attlee and his deputy, Arthur Greenwood.

Chamberlain proposed a new government, a National Government bringing together men from the opposing parties. It was a move designed to bring unity to a fractured nation, allowing it to face the war more strongly. It was also meant to end the current crisis and keep Chamberlain in power as leader of a coalition.

But the Labour leaders would not commit to a government headed by Chamberlain, indicating that their party would not support it.

Chamberlain realized that he would have to step aside.

Blitzkrieg Abroad

The following day, the situation gained new urgency. Germany launched an attack westward, invading Belgium and the Netherlands on its way to France.

The British Expeditionary Force was drawn into a far larger campaign than that in Norway, and the fate of Western Europe hung in the balance.

Chamberlain’s first reaction was to believe that his duty was now to stay Prime Minister, ensuring stability in the face of fresh crisis. But he was talked out of this by Sir Kingsley Wood, who recognized that now, more than ever, a National Government was needed.

Picking a New Leader

Chamberlain summoned Churchill and Halifax, the two men best positioned to replace him.

Chamberlain wanted to give his job to Halifax. Aside from his past clashes with Churchill, Chamberlain worried about the First Lord of the Admiralty’s performance in the Norway debate. Surely his fierce rhetoric would have lost him support among Labour and Liberal MPs.

But Halifax believed that, as a member of the House of Lords, he could not be an effective Prime Minister. It needed to be an elected MP, someone from the House of Commons.

It would have to be Churchill.

A National Government

At six that evening, Churchill went to see the King. As the new head of the Conservative Party, he was invited to form a new government.

Read another story from us: Royal Concerns: How The King Protected His Children During WWII

The King laid no obligation on Churchill to make it a National Government, but the Prime Minister knew what needed to be done. Now established in his post, he went straight to meet with the Labour and Liberal leaders.

That evening, they agreed to join him in a coalition, with members of all three parties in cabinet posts.

Parliament stood united behind the man who would prove to be one of its greatest wartime leaders – Prime Minister Winston Churchill.