After the bombing of Pearl Harbor,Berg was interested in using his language skills to help the war effort. He had, after all, studied Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Sanskrit, and Spanish.

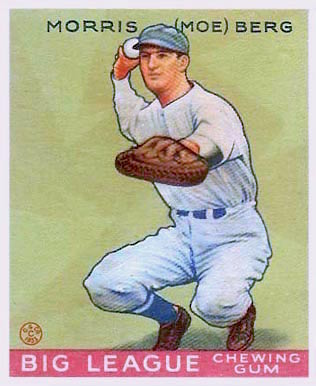

Morris “Moe” Berg was a major league baseball player, a scholar of languages, and an international spy. The combination of these factors, combined with his quirky personality, led to one of the most curious careers in the history of espionage.

Berg was born on March 2, 1902, the youngest child of Jewish Ukrainian immigrants who had eventually settled in Newark, New Jersey. From an early age, Berg had a bent for academics which eventually led to his being admitted to Princeton University.

Despite being rather isolated because of his Jewish heritage, Berg throve, becoming one of the best baseball players for the Ivy League school while earning a degree in modern languages, magna cum laude in 1923.

Berg, in fact, seemed to enjoy being apart, mysterious, and ambiguous. He wanted to live his life on his own terms. He was itinerant and wanted a career that would provide time for him to travel and continue his studies. When Princeton offered him a teaching position, he declined, picking baseball as more appropriate to what he wanted out of life.

The Most Erudite Man in Baseball

Perhaps it was Berg’s penchant for scholarship that led to a lackluster career at the diamond. For the most part, he was a second or third string catcher.

He earned a law degree while playing baseball, blowing off spring training for his studies. But he was so unique among baseball players for his erudition that the press regularly sought him out. One of his nicknames was the “Professor.” Fellow players could not figure him out.

One of his teammates with the Red Sox said, “It was very puzzling. Here was this man with a tremendous academic background in a game that didn’t call for it. I asked this to myself numerous times: why would he select the ordinary game of baseball and devote so much time to it?”

But baseball gave Moe Berg the time he needed to study and to travel. He even went to Japan twice as part of a baseball embassy in 1932 and 1934 to teach the sport. On the second trip, he took surreptitious films of Tokyo from a rooftop. After fifteen years in the big leagues playing for five teams, he retired and coached for a year.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Berg was very interested in using his language skills to help the war effort. He had, after all, studied (among other languages) Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Sanskrit, and Spanish while at Princeton, and was familiar with Yiddish and could read Hebrew. While he was not completely fluent in any of these, his aptitude for languages could certainly help in a world war.

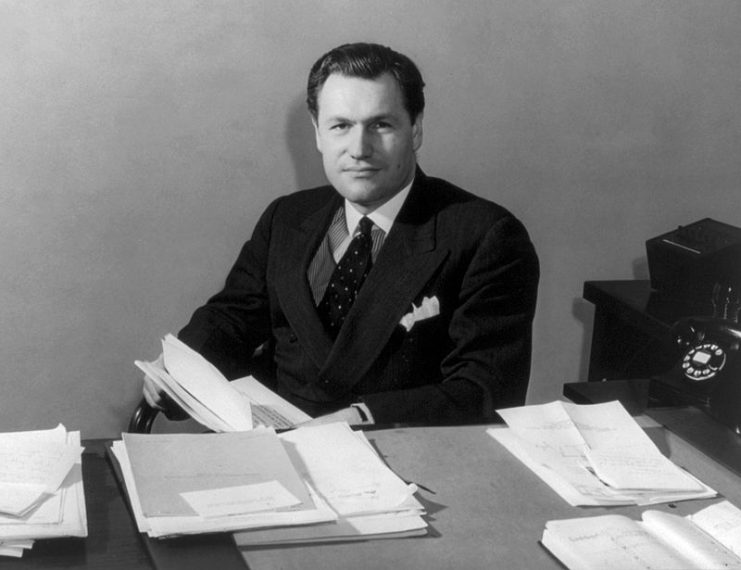

With the OIAA

Berg joined Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) on January 21, 1942. OIAA was founded in 1940 to maintain strong relations between the United States and countries in Latin America in the face of the possibility of war, and Rockefeller was its Coordinator.

As part of the war effort he even showed his movies of Tokyo to members of the intelligence community. These were appreciated, but out-of-date. Even so a persistent, false story began that Berg’s films helped plan the April 18, 1942 James Doolittle raid on Tokyo.

Berg’s time at the OIAA was more that of a travelogue and a time for him to travel in Latin America. He certainly helped the OIAA and also showed that he was not afraid of travel, going to foreign locations, and gathering information. But Berg also knew that Latin America was not where the action was. In June 1943 he resigned from the OIAA, and joined the Office of Strategic Services in August.

Moe Berg: International Spy

The training Berg would have received was intense. Typically, OSS operatives were taught such skills as safecracking, codes, ciphers, close combat, and silent killing. The whole rigmarole was taught in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland. There was even a fake house set up complete with pitfalls, dark passageways, and even a papier-mâché Hitler that the trainees had to shoot in the head.

It is unknown if Berg actually had to do all this, but it is true that as part of the training he was assigned to infiltrate and obtain intelligence from a guarded Glenn Martin aircraft plant. He failed that particular test.

Still, Berg completed the training and in September 1943 was assigned to the Secret Intelligence branch at the Balkans desk. Berg was ready to assume the glamorous role of international spy.

But the Balkans desk really was a desk job in Washington, although some accounts online have him parachuting into Yugoslavia and treating with Tito. He was actually attending to Slavic-American and Slavic-born men who the OSS recruited for dangerous parachuting missions into Yugoslavia. Berg was a bit bored with this role and desired something more.

He soon got it. On May 4, 1944, he was given $2,000, a cyanide tablet, and a .45 pistol. His mission was to learn Hitler’s atomic secrets. He boarded a plane to Italy.

AZUSA

There was great anxiety among the staff of the Manhattan Project, particularly General Leslie Groves, its head, that the Germans would manufacture and use an atomic bomb before the Americans could.

As a result, Groves had created a couple of different covert groups meant to interview foreign nuclear physicists and to look for physical evidence of Germany’s atomic program. The chief of these missions was the highly successful Alsos mission (which was independent of the OSS) and the operation Berg was assigned to, called AZUSA.

For the rest of 1944 Berg traveled, studied nuclear physics, and interviewed scientists, but never found anything conclusive. He enjoyed himself in the process, since he could travel, and did face real danger while operating in war zones.

Finally in December the OSS contemplated Werner Heisenberg, the eminent German physicist who headed Germany’s atomic program. The OSS had thought of kidnapping him in order to “deny Germany his brain.” But all the plots were too wild to execute.

Meanwhile, the Alsos Mission had found evidence in Strasbourg that indicated the Germany did not likely have or could build an atomic bomb. The operative word was likely.

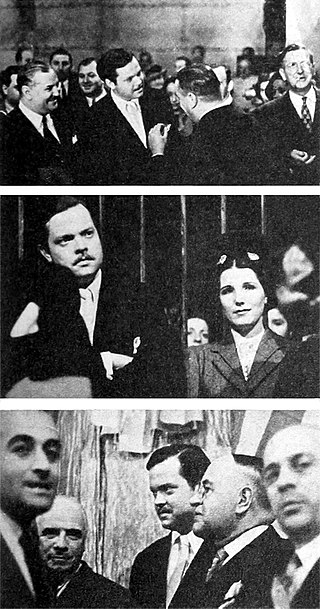

The Heisenberg Mission

Intelligence was received that Heisenberg was to give a public lecture in Zurich in neutral Switzerland on or about December 15, 1944. Moe Berg went to find out if he could tell by listening to Heisenberg if the Germans were close to building an atomic bomb. If Heisenberg said anything that convinced him, Berg was to assassinate the scientist immediately.

He arrived at the small Zurich lecture hall on December 18 (the actual day of the lecture), with an outlandish cover story that he was a Swiss physics student. Although he was 42 at the time, everybody bought it. Heisenberg began speaking at 4:15 PM.

Berg took notes. He was rather entranced that the legendary Heisenberg was right in front of him. Heisenberg took Moe Berg to be interested in the lecture. Berg was not able to follow the complex science, since his skill at German was barely passable and he was still an amateur in physics. Rather, he looked about at others in the room.

Berg jotted a note, “As I listen, I am uncertain – see: Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle – what to do to H.” While looking about he saw Carl Friedrich von Weizsacker, another well-known physicist who worked with Heisenberg.

To Berg, what he heard neither sounded threatening nor did the other people in the room seem particularly awed. It would have been highly improbable for Heisenberg to announce to a room of strangers that Adolf Hitler had an atomic bomb at his disposal anyway. There was no need to assassinate the scientist or use his cyanide tablet.

After further discussion with the physicist Paul Scherrer, a fellow attendee whom Berg had befriended, Berg concluded that Heisenberg was likely anti-Nazi. He even proposed a plan to kidnap the scientist and liberate him from Germany.

Berg also got a chance to meet the scientist at a dinner party, where he overheard Heisenberg in conversation. One person said to Heisenberg, “Now you have to admit that the war is lost.” To which Heisenberg replied, “Yes, but it would have been so good if we had won.”

Berg managed to stroll with Heisenberg after the party, peppering him with questions. It was a perfect opportunity to assassinate him. But he didn’t, and the two never crossed paths again. Heisenberg had no idea who the man was, and he would never find out.

For his work in the OSS, Berg was offered, but he refused, the Medal of Freedom. He left the OSS in 1946.

For the rest of his life Moe Berg never held a job and lived first with his brother (who kicked him out) and then his sister. He died on May 29, 1972 from a fall at home. His sister accepted the Medal of Freedom for him posthumously.

Berg was cremated and a couple of years later his urn was exhumed by his sister who took it to Israel. His final resting place is at an unspecified location on Mount Scopus, overlooking Jerusalem.