In 1939, a team of British covert agents traveled to Poland. Sent to help resist the German invasion, they arrived too late to make a difference. But their mission would prove vital to Allied operations in the rest of the war.

The Shadow of War

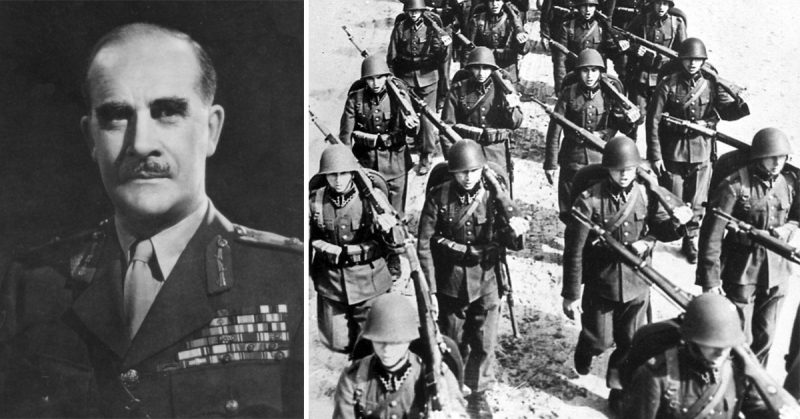

In the summer of 1939, Europe hung on the precipice of war. The British establishment, long dismissive of the threat of a major conflict, hurried to prepare for the coming storm. In an office in London, a small team led by Colin Gubbins hurried to build a covert operations unit.

On August 19, vital news reached Gubbins. British intelligence had learned that the Germans were about to invade Poland. Three days later, word of a pact between the Soviet Union and Germany made clear to the world what was coming for Poland.

Gubbins had made two previous trips to Poland, fostering links with Polish intelligence. If those efforts were not to go to waste, and if his men were to help in this opening act of the war, then he needed to act now.

Twenty Men in Suits

In a matter of days, Gubbins pulled together a team of twenty operatives, led by himself. Dressed in civilian clothes, they would travel to Europe with false passports, using covers such as an entertainer, an insurance salesman, and an agricultural expert. Their aim was to get to Warsaw, connect with the Poles, and help them prepare for a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the Germans.

The men gathered at Victoria Station to catch a train for the first leg of their journey. They had been told to dress as civilians so that they could blend in, but they lacked experience in this sort of work, and it showed.

Gubbins wore a bright green hat while one of his traveling companions had equally conspicuous tartan trousers. All of their newly printed passports bore consecutive numbers, which could have raised the suspicions of a vigilant inspector.

These would provide lessons for the future, but there was no time to correct them now. The men boarded the train and headed for the impending war.

The Long Way Around

To avoid drawing the attention of the Germans, the British agents took a circuitous route to Poland. They caught a train to Marseille in southern France, boarded a boat from there to Alexandria in Egypt, and then finally took a plane to the Polish capital of Warsaw.

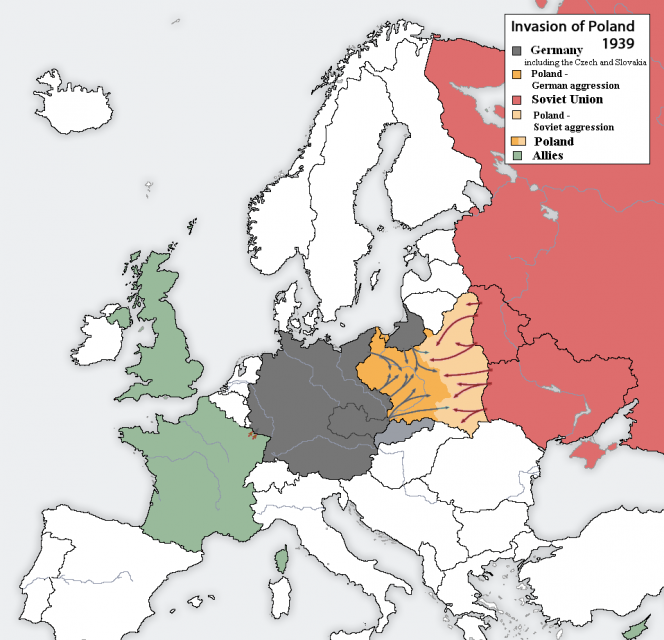

Unfortunately, the precious days it took to pull the team together and then make their drawn-out journey were the last ones of peace Europe had left. By the time Gubbins and his operatives arrived in Poland, the German attack had begun.

World War II had arrived.

Two Tragic Weeks

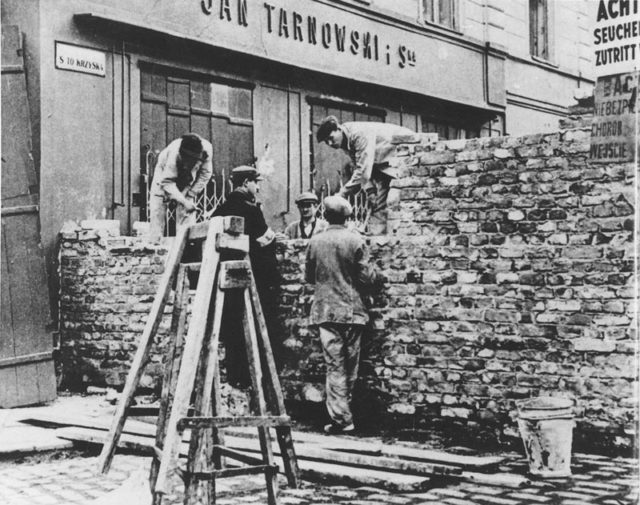

Gubbins rushed around the country, renewing old contacts, making new ones, and trying to find out how his men could help resist the German advance. He met up with the brilliant head of Poland’s Deuxième Bureau, Stanislav Gano, renewing the links between Polish and British intelligence.

He was also introduced to members of the resistance network Poland was already building as the country saw its armies swept aside.

For two weeks, Gubbins raced around Poland, frantically trying to work out what was happening and to send intelligence back to London. It swiftly became clear that his plan had been misguided. The Poles were being so decisively overwhelmed that there would be no time for guerrilla warfare, never mind time for his men to get involved.

Fleeing the Country

With the country on the verge of capitulation and Britain now at war with Germany, Poland was no place for a group of hastily assembled and ill-prepared British operatives. Gubbins gave his men the order to scatter, get across the border, and travel home as best they could.

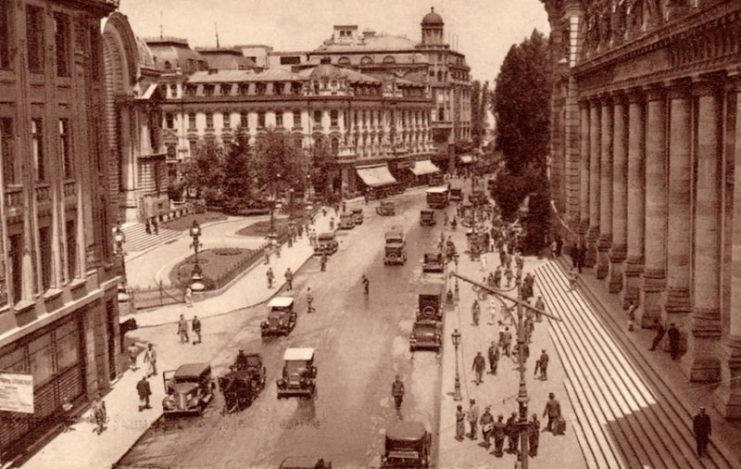

Like thousands of servicemen from the collapsing Polish forces, Gubbins headed south across the border into Romania, which at the time was neutral in the war, its independence guaranteed by the delicate balance between Germany on the one hand and Britain and France on the other. Together with one of his teammates, Peter Wilkinson, Gubbins wound up in Bucharest. There, the two Britons drank away their sorrows at the collapse of their much-anticipated first guerrilla campaign.

By October, Gubbins was back in Britain, preparing his organization for the long campaigns of intelligence gathering and sabotage that would become their war.

A Precious Prize

Though the Polish expedition appeared to many to have been a dismal failure, it led to one act that would have incredible significance in the course of the war.

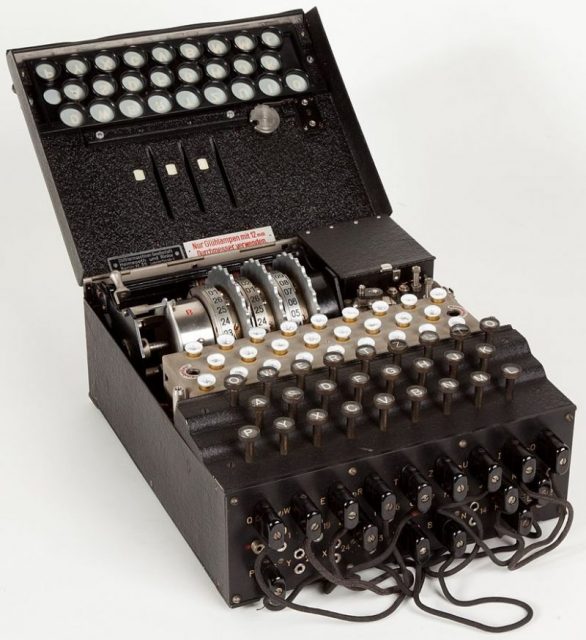

Polish intelligence had been working on cracking Germany’s military codes. Though the work was incomplete, they had made valuable progress, including the capture of a critical piece of equipment.

While Poland was being conquered, a meeting took place in the Pyry Forest, a meeting so secret that its details remain uncertain 80 years later. What we know for sure is that Polish intelligence handed a bulky leather holdall to a British agent – possibly Gubbins himself.

Read another story from us: The Invasion of Poland in the Opening Stages of World War Two

This was passed on to another Briton, Wilfred “Biffy” Dunderdale, who transported the contents of the bag safely back to Britain. So critical was this item that it was met at Victoria Station by the head of MI6.

This was the Enigma machine. Its decryption would allow the Allies to read high-level German communications throughout much of the war, regularly saving lives and altering the outcome of the conflict. That work was made possible thanks to Gubbins’ failed Polish guerilla war.