The British National Gallery in Trafalgar Square is a must-see during any tourist trip to London. If you should be lucky enough to visit today you will see works by Titian and Van Dyke, but had you been there in 1942 it would have been a different story. During the Blitz and subsequent bombing raids, the gallery was hit nine times, completely destroying the Titian Room.

However, almost all of the collection survived the war in a place even Hitler’s Luftwaffe couldn’t reach: Manod Quarry, deep in Snowdonia in the Welsh mountains.

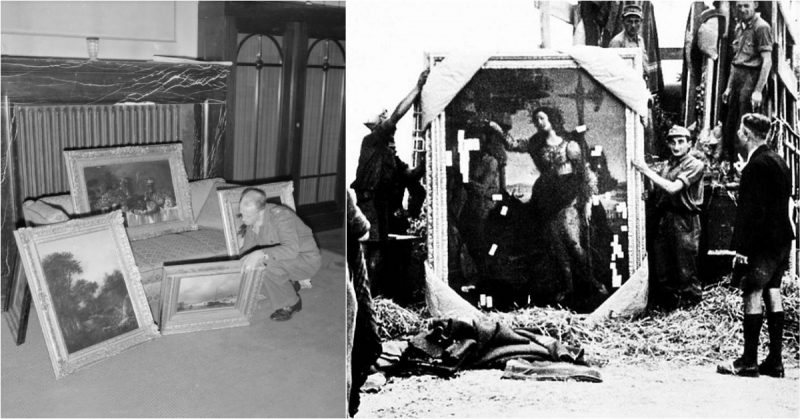

While the German war machine was raging across the European continent, looting, burning, or bombing irreplaceable works of art in the process, Kenneth Clark, the director of the National Gallery at the time, organized evacuation of the collection.

After the Munich Crisis of 1938, it was suggested that perhaps the national collection should be transported to Canada for safekeeping. However, the outbreak of war made U-boats a threat to that course of action.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill reportedly said of the collection that Britain should “Hide them in caves or cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island.”

Until a secure hiding place could be made ready, the collection was split up and sent out of London to stately homes across west England and Wales. Most items were stored at Penrhyn Castle, Bangor University, and the National Library of Wales at Aberystwyth.

Unfortunately, these sites were on the German long-range bomber flight path between northern France and the port of Liverpool. It was this very real threat from the Luftwaffe that eventually led to the quarry at Manod being opened up and discovered to be big enough to house the entire collection.

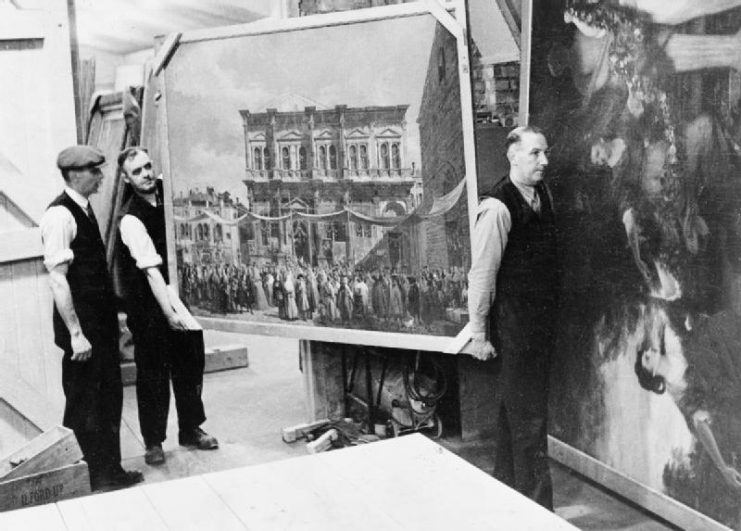

Some chambers were over 100 feet tall and were linked by a maze of tunnels and drainage channels. Even so, some 5,000 tonnes of material had to be cleared to make way for the paintings, and an access road had to be lowered under a railway bridge so that trucks could get through.

Inside the slate quarry, government contractors built brick rooms that could be lighted and properly temperature controlled so that conservation work could carry on uninterrupted.

By August 1941 the secret storage location was ready and the art works began to be stored within the Welsh mountain. An added bonus of the operation was that the entire collection could be cataloged for the first time.

As the war ground on, the gallery directors adopted a practice of returning a single work of art every month to remain on display before its return to safety. This was a propaganda exercise and also a morale booster for besieged Londoners. It proved so popular that today the National Gallery has a “painting of the month” feature on its website.

By the summer of 1941, the entire collection had been delivered to its secret subterranean home. It remained at Manod for the remaining four years of the war.

After the war, the lessons learned with regard to air conditioning and controlled environments were able to be included in plans for the refurbishment of the bomb-damaged gallery in Trafalgar Square. The Scientific Department formed between the wars was also then merged with the newly formed Conservation Department.

Manod was kept on by the British government as a “prepared quarry” in case of war right up until the 1980s, when government policy changed and anything not dedicated to the preservation of the state was sold.

Alfred McAlpine took over the site and employed modern open-cast quarrying techniques, exposing some of the chambers and removing part of the top of the mountain.