“We’re the battling bastards of Bataan;

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam.

No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces,

No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces.

And nobody gives a damn.

Nobody gives a damn.”

-Frank Hewlett, 1942

Waving the White Flag

April 9, 1942 – Major General Edward P. King surrendered his Bataan troops, some 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers, with their well-being in mind. He saw how these servicemen were fighting with almost nothing to eat [half rations were cut in half and half again as the days of fighting dragged on for months]. He saw how ill they were from diseases brought about by malnutrition and the tropical forest surrounding them. Most of all, he saw how they fought with almost no ammunition. He didn’t want them to die slaughtered brutally at the hands of the Japanese. He must have believed that with the bravery his soldiers showed, they would be, at the least, treated with a little respect by the enemies.

The Japenese were enraged at the Allies for making the Battle of Bataan difficult. Furthermore, the Japanese culture at that time viewed warriors who surrender without honor and were not fit to be treated as humans. To say that they were not kind to the POWs was an understatement. They acted barbarically. One of the atrocities they committed against the captured Allied troops was the Bataan Death March.

Bataan Death March: March to Hell

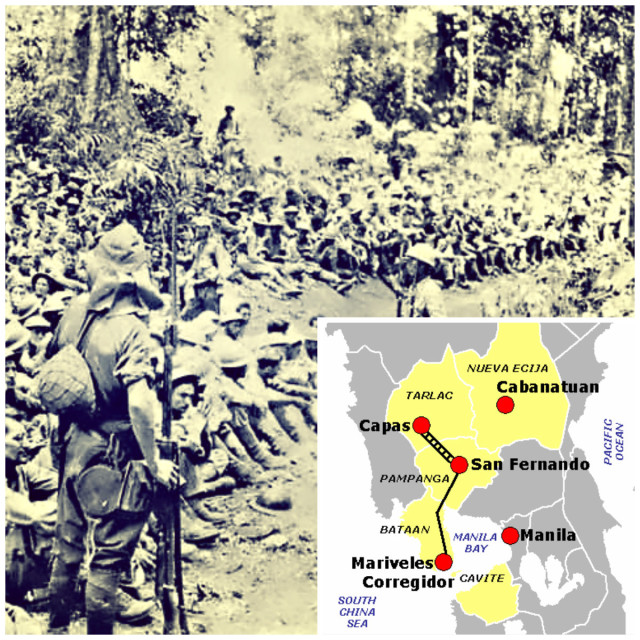

Right after the formal laying down of arms, the Japanese soldiers rounded up their American and Filipino counterparts and forced them to march from Mariveles, Bataan [which was at the southern tip of the Bataan peninsula] to San Fernando, Pampanga. From there, they were crammed inside “hell boxcars” and transported via train to Capas.

Then from , Capas, the POWs walked a further 7-mile stretch [about 11 kilometers] to Camp O’Donnell, formerly a training center for the Philippine army but was converted by the Japanese as an internment camp for captured Allies.rom , Capas, the POWs walked a further 7-mile stretch [about 11 kilometers] to Camp O’Donnell, formerly a training center for the Philippine army, but was converted by the Japanese as an internment camp for captured Allies.

From , Capas, the POWs walked a further 7-mile stretch [about 11 kilometers] to Camp O’Donnell, formerly a training center for the Philippine army, but was converted by the Japanese as an internment camp for captured Allies.

While most of the soldiers started the death march right from Mariveles, some joined the throng along the way. The dismal walk ranged from 5 to 10 days depending on where one started. Throughout it, one thing remained — the brutal way the captors were treating their prisoners of war.

Aside from having little to no water to drink and no food to eat, captured soldiers who lagged behind their groups because of their weakened state and exhaustion, those who stop for water and those who tried to escape were either beaten, shot, bayoneted or beheaded. Some Japenese also did these just for sport.

When transported to Capas, after the main death march, the captured soldiers were loaded by the hundred in an unventilated train car that had the minimum capacity of only 40. Arriving in Capas, they once again trekked the rest of the way to Camp O’Donnell on foot where they were interred – Filipinos and Americans separated – and subjected to more brutalities.

Bataan Death March: Counting Death

Ultimately, the exact number of deaths during the death march and the imprisonment that followed it are not known. Accordingly, some 500 Americans and up to 2,500 Filipinos died in the main march. In the prison camp, it is believed that as many as 1,500 Americans and 26,000 Filipinos died due to illnesses and starvation. All in all, of the approximately 22,000 American soldiers captured by the Japanese during the Fall of Bataan, only about 15,000 were able to return home to the States.

Death rate was calculated at 40%. At this rate, POWs captured by the Nazis and other Axis allies throughout WWII fared better in comparison with only a death rate of 3%.

Bataan Death March: Not Singular

The Bataan Death March was not a singular event. The Japanese Imperial Army conducted various death marches in the countries they invaded and conquered. These led to the deaths of thousands of not just American, British, Dutch and Australian POWs.

However, news about these death marches was withheld as the Allied forces back home feared the Japanese would retaliate against the POWs if they were leaked to the public.

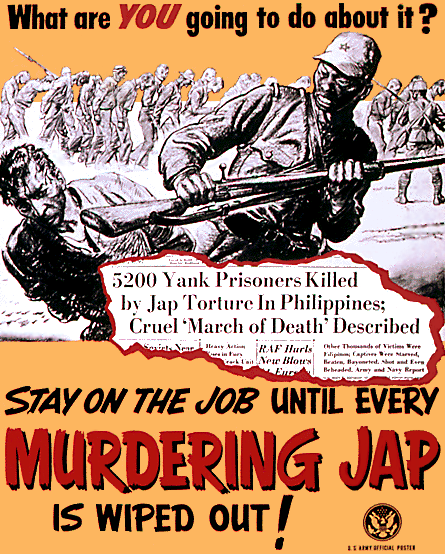

It was only in January of 1944 when news about the atrocious death marches, through the testimonies of soldiers who were able to escape alive, were announced as part of the launching of a war-bond drive. The goal of the announcements was to reignite the fighting spirit of an America wearied by the war.

Aftermath

When WWII ended, Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma, the Japanese commander in charge of the invasion and conquest of the Philippines, was tried for the many atrocities the Japanese did during the march and internment at Camp O’Donnell. He was found guilty and was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.