By late 1944, Germany was undoubtedly losing WWII. Its forces were being driven back on every front, often in great disorder.

When they were compelled to withdraw from Finland, the Germans encountered new difficulties. Rising to the challenge, they achieved an orderly and successful fighting retreat, at odds with the chaos and confusion on other fronts.

Finland in World War Two

Finland did not side with Nazi Germany due to dreams of conquest, as Japan and Italy did. The Finns allied with Germany to defend themselves. In November 1939, while Europe was rallying to fight Hitler, the Soviet Union invaded Finland.

The Winter War was an embarrassment for the Russians. Their forces were not equipped for the terrible harshness of the Finnish winter. Fuel froze in vehicles. Men died of cold and exposure. Their advance eventually stalled in the face of determined Finnish resistance.

It was not a complete failure. By March 1940, at the end of the campaign, the Soviets occupied a tenth of Finland, including a disproportionate part of the country’s economic base.

When the Germans turned on their former Soviet allies and invaded Russia, it was natural the Finns would side with them. Taking the opportunity, Finnish troops drove the Russians back to their original border.

Then the Finns stopped. They had recovered their lands and did not want to take on the risks involved in invading Russia. They remained allied with Germany. German troops moved into Finland, providing protection in return for access to valuable resources such as the nickel mine at Kolosyoki.

The Decision to Give In

The Finns resisted Russian attempts to break their alliance with Germany but by the fall of 1944, their position was becoming untenable. The Russians were pushing back the Germans across the Eastern Front. Finnish casualties were mounting.

Marshal Mannerheim, Finland’s military leader, explained his position in a letter to Hitler. Germany was a great nation which could afford to fight to the last, in the knowledge that it could bounce back from a significant defeat. Finland was not. If it was overwhelmed, then the country’s very existence might come to an end.

So the Finns made peace with Russia. As part of that agreement, they had to break off ties with Germany and expel all German troops.

The Difficulty of Withdrawal

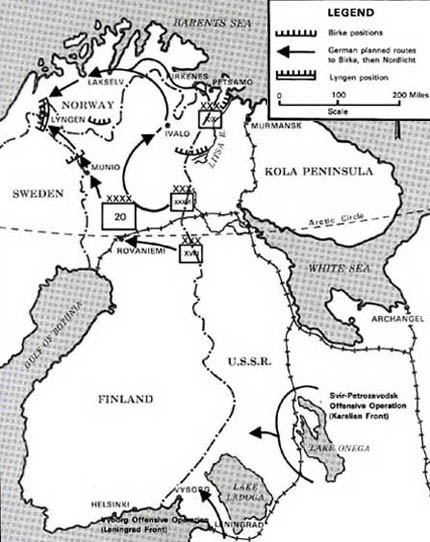

Three corps of German troops were based in Finland under General Lothar Rendulic. They had two weeks to get out, after which they would be subject to attack by the Finns.

It was an impossible challenge, and Rendulic knew it. Troops based on the coast could be shipped out on time, but not the rest. Those in the center and the high north would have to be brought out along an inadequate road network. With nearly a quarter of a million men and all their equipment at stake, it could not be done within the time limit.

Added to the difficulty was the fact that winter was closing in. The cold and damp that had beaten the Soviets five years before would become Rendulic’s enemies, making roads impassable and living conditions unbearable on the march.

The Forced March

As was so often the case, Hitler found a way to make his subordinates lives even more complicated. Rendulic was ordered to hold onto the Kolosyoki nickel mines for as long as possible. It meant the area could not be evacuated until the last minute. Troops retreating from there would face a forced march.

The same applied to troops based at Rovaniemi. That town sat on several of the evacuation routes. If the Germans lost control of it, then it would become impossible to withdraw safely. Rovaniemi had to be held until the last.

Planning the departure took time. As a result, Operation Birch Tree, the first phase of the withdrawal from Finland, started on September 3; the date by which the Finns had demanded the Germans leave.

Divisions based in southern Finland started the retreat. Marching north, they began a vast reverse arc in which hundreds of thousands of men made their way toward their rallying point.

Fighting Retreat

The forced march quickly turned into a fighting retreat.

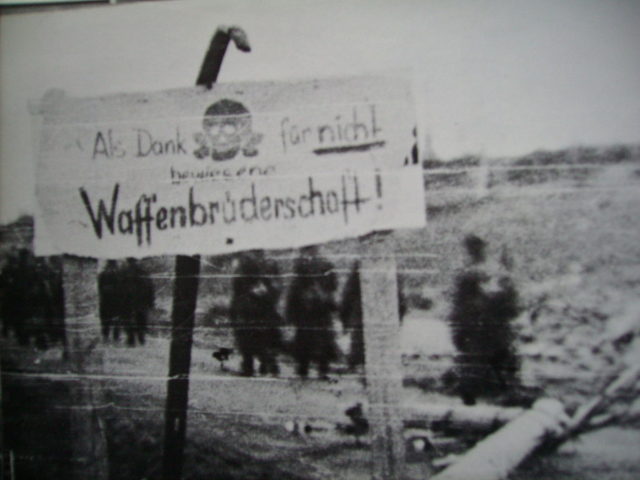

To meet their agreement with the Soviets, the Finns could not accept the presence of German troops. Finnish units attacked their former allies as they marched through the dark and sodden forests.

Meanwhile, the Soviets made their move. The Red Army launched a series of offensives designed to take Rovaniemi and cut off the roads around it. At stake was a large part of the German army, which would be cut off if those roads fell. The Soviets did not want their enemies returning to the Russian Front.

The fall of 1944 was exceptionally cold and wet. The Germans suffered repeated attacks and terrible weather as they spent weeks on the march. The rearguard clung to Rovaniemi to let the rest through.

“You Have Saved Germany’s Best Army”

At Karaguendo, near the Swedish-Lapland frontier, the German XVIII Corps stood on guard. Their job was to keep the border open for their comrades, holding the line until the whole army was out.

It was a long wait. The operation lasted until late December, some troops spending over three months caught up in the withdrawal.

Rendulic’s preparations paid off. Despite all the circumstances against them, he successfully got his forces out. When he met with Hitler on January 17, 1945, the Fuehrer congratulated him. “You have saved Germany’s best army,” he said. “To be honest, I did not think that such a feat as you have carried out could be accomplished.”

Under Rendulic, it could be done, and it was.

Source:

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers: Leaders of the German War Machine 1939-1945

Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders