From the start of the Second World War, Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF) committed themselves to a particular bombing strategy. They believed that, with heavy and persistent enough bombing of German targets, Britain could win the war.

As the war progressed, it became apparent the strategy was not effective. It led to a change of tactics with Operation Millennium, Britain’s first thousand-bomber raid.

The Bombing Strategy

In the generation since it had originated, the RAF had developed firm traditions and beliefs. One of these, planted by the RAF’s first head Lord Trenchard, concerned the place of bombing in war.

Trenchard believed overwhelming aerial bombardment could win wars. The role of bombers was to pound strategic targets into rubble, ending the enemy’s ability to fight. It would bring victory from the air.

Critically, the RAF, and in particular Bomber Command, believed they could deliver this. In their opinion, the people and equipment they had would be able to bomb Germany into submission.

This was the strategy Britain entered the war with. Initially, only military installations were targeted. That changed on August 24, 1940. Then, at the height of the Battle of Britain, a German bomber accidentally hit a civilian target. Taking the excuse, Churchill turned the RAF to terror bombing German cities. The Germans did the same, both sides aiming to intimidate each other’s populations and destroy morale.

Evidence of a Problem

Britain’s bombing campaign against Germany continued through 1941 and into 1942. It was a costly exercise in men and material, with planes regularly being shot down by German fighters and anti-aircraft guns. Bomber Command persisted, confident they were severely damaging the Germans. Unfortunately, they were not.

At the start of the war, it was partly due to equipment. The bombs used were not large enough to damage German production substantially. Many of the planes could not carry bigger bombs. British guidance systems were behind those of the Germans, meaning bombing was wildly inaccurate. Also, vital intelligence needed to direct the campaign was missing.

As aerial photography improved, it revealed the damning evidence. Photographs showed that 90% of bombs were not falling within five miles of their targets. The damage was not being done.

At first, Bomber Command insisted the photos could not be relied upon. When Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris took over command in early 1942, it was evident a change of tactics was needed.

Operation Millennium

What Harris came up with was Operation Millennium. Instead of sending lots of bombing raids against different targets, he would launch a single strike by over a thousand bombers. The vast number of planes would overwhelm German air defenses, reducing casualties for the British. A massive attack on a single target would provide the sort of destruction Bomber Command had always claimed it could achieve.

Every plane and pilot the RAF could get hold of were utilized. A last-minute change of heart by the Admiralty meant that planes used to target submarines could not be borrowed from the Navy. Instead, trainee pilots and barely serviceable planes took their place.

It was to be an overwhelming display of power and set the tone for future bomber runs. All being well, it would also save Harris and Bomber Command from negative scrutiny.

The First Raid

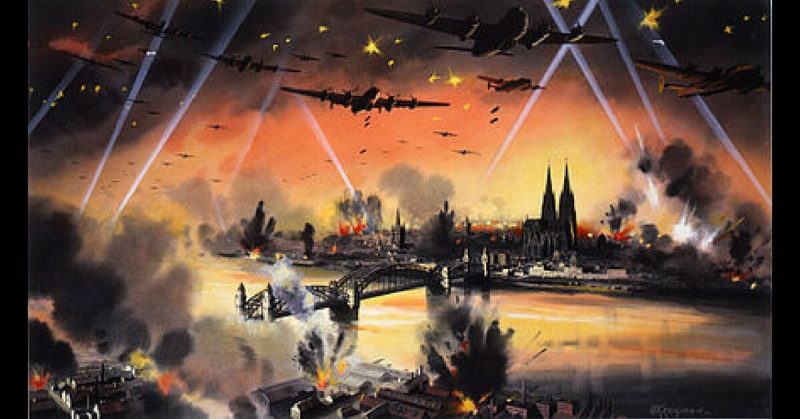

On the night of May 30, 1942, 1,047 bombers took off under cover of darkness from British air bases.

There was a last-minute change of target. Initially, the thousand bomber raid was heading for Hamburg, to smash the port and naval facilities there. As well as a major German city, Hamburg was a legitimate military target. However, weather conditions meant the attack could not occur there.

Instead, Cologne was targeted; Germany’s third largest city but not one of its leading industrial centers. For all the talk of strategic purpose, this was primarily a terror raid.

One of the challenges was allowing so many bombers to reach a single target while minimizing German intervention along the way. To this end, the pilots flew in tight linear formations along pre-determined routes. The planes had to fly at a range of pre-determined heights using the latest navigational equipment to prevent them crashing into each other.

With so many planes in a small space, it was envisaged German air defenses would be overwhelmed.

A Success of Sorts

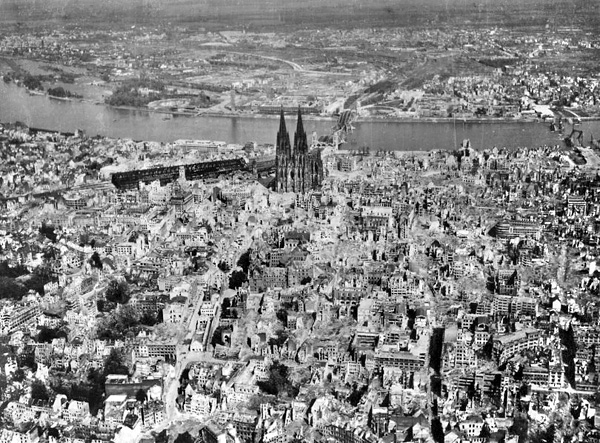

Operation Millennium was a success, from Bomber Command’s view. In the course of 90 minutes, over a thousand planes dropped bombs, primarily incendiary devices, on Cologne. Both their air defenses and firefighting teams were overwhelmed. The aim was not precision bombing but mass destruction, which happened.

411 civilians and 58 German service personnel were killed. 5,000 more were injured, 45,000 made homeless, and nearly 700,000 fled the city in the aftermath.

The psychological impact was incredible, terrifying Germans and lifting the hearts of Jews who heard of it while trapped in the Warsaw ghetto. The Germans were feeling some of the pain they had inflicted on others.

Casualties among the bombers were a relatively light 4% – Churchill had considered 10% an acceptable cost on this mission. The destruction and mental impact seemed to prove the RAF’s point. A dozen more raids like it followed, including Hamburg. In less modern cities, incendiary bombs led to destructive firestorms.

It was the sort of attack that made Bomber Command controversial during and after the war. Of minimal impact on military and industrial installations, the supposed targets of war, but terrifying for enemy populations.

It proved that mass bombing could achieve its goals. Whether they were legitimate goals remains contested to this day.

Source:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War.