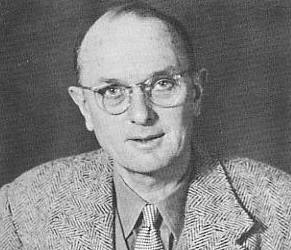

During the Second World War, Allied prisoners of war (POWs) were greatly helped in their escape attempts by MI9, a secretive department of the British government. The man in charge of those operations was Norman Crockatt.

A Seasoned Veteran

Norman Crockatt was born on the 12th of April 1894, just in time to complete his education and begin a military career before the First World War started. He went to the prestigious Rugby school and from there to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. In 1913 he joined the Royal Scots, the oldest regiment in the British Army.

When war broke out in 1914, Crockatt was a lieutenant. He served with distinction in France and Palestine, was mentioned in dispatches three times, and earned both the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and the Military Cross (MC). He was severely injured in action.

After the war, Crockatt remained in the army until 1927. When war broke out again in September 1939, he returned to uniform, ready to fight again for king and country.

Recruitment

In the autumn of 1939, British military intelligence was hastily rebuilding following inter-war neglect. One area of operations being considered concerned POWs. This would involve helping Allied POWs to escape prisoner camps and using POWs from both sides as sources of intelligence.

Major J. C. F. Holland, a senior figure within Military Intelligence Research (MIR), was asked for his advice on who could head up this new operation. Rather than pick someone who had experience as an escapee, he suggested someone he had worked with at MIR – Crockatt.

Crockatt had a good reputation. He was quick-witted, clear thinking and an excellent organizer. He had a talent for judging the character of the people around him. Critically, given the unconventional and controversial role he was about to take on, he wasn’t the sort to let himself be restricted by red tape.

As so often in the British establishment, progress depended on a mixture of skills, experience, and who a person knew. Now Crockatt had progressed to the leadership of an important new department in just such a manner.

Aims and Objectives

Crockatt, now a major, was put in charge of MI9, the new organization responsible for POW work. As head of the unit, he had five objectives:

- Help British POWs escape, to get them back into action, and use up enemy resources trying to stop them.

- Helping British troops who had evaded capture in enemy territory to get home. After the fallout from Dunkirk, this mostly concerned airmen who had been shot down.

- Collecting and distributing information gathered via POWs.

- Denying such information to the enemy.

- Maintaining the morale of British troops in captivity.

A Small Team

Many bureaucrats try to build large empires, with as many staff as possible. Crockatt preferred to surround himself with a small but carefully chosen group.

Key personnel in his department included:

- Captain A. R. Rawlinson, who had briefly run MI1, a predecessor of MI19 concerned with intelligence gathering from POWs.

- Christopher Clayton Hutton, an eccentric army veteran, pilot, and inventor, who specialized in creating devices to help prisoners and escapees.

- “Johnnie” Evans, author of one of the best books on prisoner escapes of the First World War, The Escaping Club

Over the course of the war, the team inevitably grew, but it always remained focused on such experts.

Training

Crockatt set up specialist training courses to prepare men for escapes. Pilots, in particular, were given advice on how best to evade capture or get out once the enemy had them.

These training courses covered a wide variety of topics – how to disguise yourself as a local; how to find friendly contacts; how to avoid detection; how to behave when captured. They allowed pilots who had been shot down to evade capture and connect up with the escape lines, resistance networks that could get them out of Axis-occupied territory.

Equipping

Crockatt had Hutton and the men around him develop an ingenious range of devices for evasion and escape.

Some of these were given to men before they went into action. Pilots carried hidden documents in their boot heels and buttons, wire saws in their laces, and pen tops magnetized to act as improvised compasses. Uniforms were designed so that they could be converted quickly into civilian clothes. These helped many servicemen to avoid being caught and find a way home.

Other devices were sent into the prisoner camps. Maps were disguised as handkerchiefs, while parts of radio sets were hidden in innocuous packages. These tools helped POWs prepare their ingenious escape attempts.

Coordinating

Critically, Crockatt coordinated the disparate elements involved in escapes. Contacts with the resistance allowed him and his department to establish safe escape lines out of France and the Low Countries. Covert radio contact with prisoners in camps meant MI9 could learn about what they had seen behind enemy lines, as well as providing guidance on escapes.

Limits

Aside from the challenging nature of the work, there were limits on what Crockatt could achieve. He was worried about putting prisoners’ lives in danger by pushing the enemy too far and didn’t want to risk turning POWs into bargaining counters for extremists on the Axis side.

He was also restrained by the interests of other organizations. MI6 particularly disliked any scheme that they thought might interfere with their agents.

Growth and Promotion

Despite these limits, Crockatt flourished in his role. In 1941, he was made a colonel and then Deputy Director of Military Intelligence (Prisoners of War). His department grew and became the inspiration for similar American efforts.

Crockatt ended his military career as a brigadier. Following the war, he ended up as a stockbroker and director of an oil company. He died on the 9th of October 1956 after a distinguished career. Thanks to his work, many other British soldiers were also able to survive the war.