WWII did not end with Hitler’s suicide. As the Allies advanced across Germany from east and west, soldiers were attempting to find the safest places to surrender. Some were fighting to the bitter end. Others, like the Der Fuehrer Regiment of the Das Reich Division, were struggling to salvage what they could from the collapse.

Dying Days

Led by Otto Weidinger, Der Fuehrer was an SS Regiment. They had spent most of the duration of the war fighting on the eastern front, in fierce combat against the forces of the Soviet Union.

By the last month of the war, the Das Reich Division was scattered across the eastern front. During a frantic reorganization undertaken to attempt to hold back the Soviet tide, its regiments were divided into individual battlegroups.

Der Fuehrer had been part of a fighting retreat through Hungary and Austria. They had defended Vienna before its fall. By late April 1945, they were in southern Czechoslovakia awaiting orders to join the divisional headquarters group.

Instead, on April 30, Weidinger received a summons to Prague. There, he met with the region’s SS Supreme Commander, Obergruppenfuehrer Pueckler. He told Weidinger that Prague was calm, but it did not mean it was safe for the German civilians and soldiers based there. Plans were underway to evacuate the Germans.

Approaching Prague

Weidinger returned to his regiment. He held a parade at which he announced the news of Hitler’s death. He reminded his soldiers that they were still bound by their oath of loyalty to defend their country. They would fight on until the war ended.

Then a message arrived from Field Marshal Schoerner. A revolt had broken out in Prague and the surrounding region. Weidinger was to take his forces there immediately to put down the insurrection.

On May 6, Weidinger and his battlegroup set out for Prague. It was an arduous journey. Along the way, they encountered German soldiers who had been disarmed by Czech partisans who were putting up a growing resistance.

It reinforced the need to get the Germans out of Prague. German forces, and particularly the SS, had been responsible for terrible atrocities in Czechoslovakia. The entire village of Lidice had been wiped out in reprisal for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. The Czechs were understandably angry at their occupiers. Innocent and guilty alike, any Germans in the area were in danger if the Czechs captured them at the end of the war.

The Attack

In the suburbs of Prague, the battlegroup met their first major obstacle – a huge roadblock made of cobblestones. It could not be bypassed or blown up, so Weidinger set his men to work dismantling it. They worked late into the night making a gap big enough to drive through.

Then, with headlamps blazing, they raced toward the heart of the city, but at the Troya bridge, they came under fire from small-arms.

It was too dark to see who was shooting and Weidinger could not advance without returning gunfire. As the war was almost over if his men hit civilians, they would face trials for war crimes. They waited tensely until first light when the group could safely target enemy combatants.

At dawn on May 7, Weidinger’s artillery opened fire. Under cover of the bombardment, grenadiers stormed forward, frightening off the Czechs.

A brief ceasefire followed, during which Weidinger realized his enemies were playing for time. He restarted the attack, taking the bridge and also land on the other side.

He gathered his men, ready to head deeper into the city.

Negotiations and Preparations

A Czech officer emerged, willing to negotiate between Weidinger, the partisans, and the German commander inside the city. Weidinger sent an officer with him to negotiate but warned that if there were no result by 1500, then he would feel free to advance by force.

During the lull in the fighting, Weidinger sent patrols out to gather weapons, ammunition, and supplies. They found a fuel dump near their perimeter, allowing them to fill the tanks of their vehicles.

1500 passed without a response. Weidinger waited another hour.

At last, the negotiators returned.

Too Many People, Not Enough Trucks

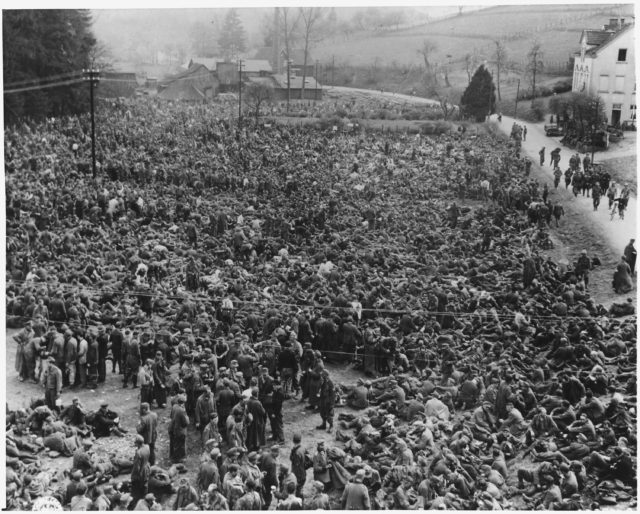

An agreement had been reached. Weidinger could take the Germans out of Prague. The locals would clear his way and provide directions to Pilsen, where he and his men could surrender to the Americans. It was the wish of most German soldiers – imprisonment in the west rather than the east.

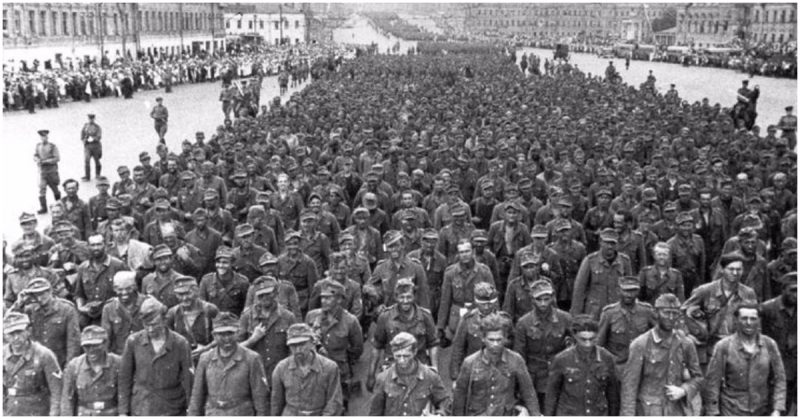

Weidinger faced a new problem. News of his arrival was drawing in German troops from across the area. The soldiers were afraid of being left in Czech or Russian hands. There were not enough vehicles to transport everyone.

As the day progressed, the situation grew worse. Ambulance trains full of wounded German soldiers were found at railway sidings. A large group of women who had worked as SS signaling staff arrived. The convoy was growing with each passing moment.

A Tense Journey

Weidinger did his best to find transport. As his column rolled out late on May 8, it consisted of a thousand lorries.

On the route to Pilsen, they encountered a German general and a Czech colonel, who ordered them to hand over their weapons. They did so and then dropped off the civilians and wounded at Pilsen.

Weidinger held a final parade for his unit. Food was distributed to the remaining men. Then they got into trucks and drove to Rokiczany, where they surrendered to the 2nd US Infantry Division.

They had fulfilled their final mission. At last, the war was over.

Source:

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers: Leaders of the German War Machine 1939-1945

Russell Phillips (2016), A Ray of Light: Reinhard Heydrich, Lidice, and the North Staffordshire Miners