Mark Barnes continues his adventure with a look at sacred spots for both Turkey and Australia on the battlefield.

As the Australians poured ashore at Anzac a little known Turkish staff officer looked for the means to respond. Having enjoyed high quality German training he knew that it was essential to throw in a counter-attack to disrupt the invaders and keep them off balance, maybe even throw them back. Mustafa Kemal looked to the 57th Infantry Regiment, telling them:

I am not ordering you to attack. I am ordering you to die. During the time before we die other forces and commanders will take our place.

The regiment is remembered today at a feature of the battlefield known as the Chessboard where a memorial and representative cemetery stands. It was built in 1992 and features a tower, a memorial wall and the “graves” of some of the eighteen hundred men of the regiment who are known to have died. At the entrance stands the statue of the last surviving Turkish veteran of Gallipoli, Huseyin Kacmaz, who is depicted holding hands with his granddaughter. Just down the hill are some of the genuine graves of men of the 57th. It seems obvious that the architects were anxious to create something on par with some of the majestic burial grounds of the CWGC and in this they have succeeded.

Most admirably there were a large number of Turkish visitors and this was repeated at many of the sites we visited. They are proud of their history and in the national psyche the men who successfully defended the peninsular from the Allied invasion are martyrs. I walked up to stand under the tower. Looking up from the base had an effect not unlike an MC Escher drawing and I think he would have liked the effect. Many of the Turkish memorials built in only the last twenty years or so and have a modern feel that distinguishes them from the sites devoted to the invaders built between the two world wars.

To emphasise this you only have to cross the road to marvel at a huge statue named Respect For the Turkish Soldiers – they were all known as Mehmet, a popular name in the vein of Tommy Atkins. At Gallipoli the British and Anzac troops were known as Johnnie by the Turks. The statue was installed in 1992 and was made by the sculptor Tankut Oktem. I have to say I really like this statue. It was one of many really attractive works found on the battlefield.

This stop off allowed me to buy a replica Turkish soldier’s hat from a stall before enjoying a much-needed ice cream. We got on our bus and headed to The Nek.

For many people their entry point, or even their whole knowledge or assumptions about the Dardanelles campaign come from Peter Weir’s Gallipoli. The climax to the movie is a version of events at The Nek where the 3rd Light Horse Brigade carried out an ill-starred assault on part of the Turkish line on 7th August 1915. The film’s representation of the battle is widely accepted to be inaccurate, but movies have a way of setting things in stone for some minds. The attack was a tragic and seemingly pointless disaster and once again at Gallipoli senior officers went into the assault when they should have been more circumspect.

The campaign is littered with examples of immensely brave British and Anzac officers losing their lives for often futile gestures rather than putting their positions of responsibility at the head of their priorities. Honour and the chance of glory were always to the fore in their thinking and the damage this did to the coherence of their units was immense and sadly quite unnecessary.

Given the risible quality of top level planning at Gallipoli it seems difficult to appreciate there was a link between the attack on The Nek and events at Suvla Bay where the newly formed British IX Corps under the command of the hopeless Lt Gen Frederick Stopford had landed the day before. At The Nek the 8th Light Horse went over in two waves and were shot to pieces by the Turks who were aware a charge was imminent because an artillery barrage had stopped some minutes earlier. The attack was not delayed as such, it was bedevilled by errors, poor coordination meaning the men going over the top should have set off immediately the barrage stopped. Crucially, the watches of the officers leading the assault and the artillery were not synchronised and the lost minutes would prove calamitous for the 8th Light Horse.

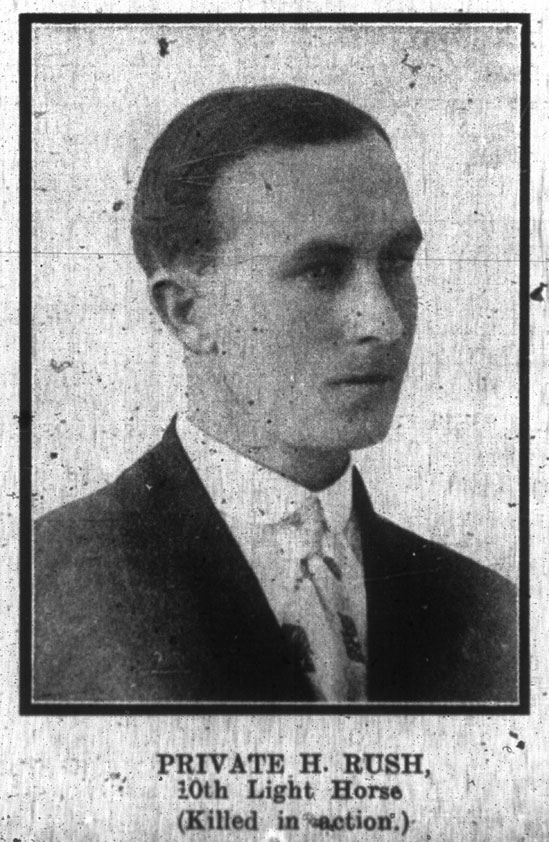

A third wave faired no better but by this time attempts were being made to stop a fourth wave making the assault. Regardless of this, some men on the right of the 10th Light Horse went over anyway even as their commanding officer was calling a halt to the attack. Over three hundred men from the 8th and 10th had died in a matter of minutes, the majority barely able to advance a matter of feet from their trench before they were cut down.

The attack was to have involved a separate approach by a New Zealand battalion, coming up on the Australian right flank but they were much delayed by a wayward approach march imposed by the planners and the loss of time meant they never even got started.

It is astonishing how small the battlefield of The Nek is. The Australians had to cross thirty metres to reach the Turkish trenches on a frontage of little more than a hundred and fifty metres. The cemetery at The Nek covers a good deal of this ground and standing in it’s boundary the area doesn’t seem much bigger than a couple of tennis courts in my local park. Charles Bean, the distinguished Australian official historian put it at three. All but a few burials are unidentified. The dead were not recovered after the fateful attack and had been lying where they fell for some years before their recovery.

Regardless of the contentious bits I have always enjoyed Gallipoli as a movie and I can separate the factual errors from a good story well told. Unfortunately it is cited as accurate history on some websites that appear to get their geography wrong by mixing up the expanse of Ocean and North beach with distant Suvla where the British landed. One version even says the British could clearly be seen drinking tea. While too many Brits were dithering about in line with useless orders whoever saw them sipping Darjeeling from the position of The Nek must have had a bloody big telescope.

There is no question that events at The Nek added to the growing sense of a national identity in Australia and other battlefields would propel the process. But any implication that the woeful direction of the flawed campaign by Hamilton and other lesser mortals was solely the cross of Australia to bare misses the point that their dismal strategy was lethal to anyone in their charge, Brits, Aussies, Kiwis, Newfoundlanders and Indians. Cemeteries across the peninsular prove this.

For the second time in the day we were able to walk in front line trenches and once again the smothering of dense brush was obscuring many more features it would have been nice to see. Someone remarked that the place needed ‘a good fire’ and as odd as it sounds for the budding historian this is probably true, while anyone looking at it from the perspective of a naturalist (or a fire-fighter for that matter!) would most likely think the complete opposite! The usual habit of some of my chums for spotting relics continued and the odd bullet made an appearance.

Just beyond The Nek is Walker’s Ridge where an eponymously named cemetery is the last resting place of some of the Aussie casualties of 7th August 1915. From here our party split into two groups. The walking wounded and the sensible people (often a mixture of the two) would go by bus down to Anzac Cove while the criminally insane would make their way down Walker’s Ridge, itself, to the sea.

I was on the bus.

Our chief guide and pub singer, Peter, had described the ridge in less than glowing terms (to me at any rate) as a precipitous path with huge sheer drops on either side. As someone who tends to get dizzy climbing a stepladder to change a light bulb this was not an advisable adventure for me to attempt. I had a discussion with my mate John about it only a few days ago and he confirmed there was no way I could have done it and seemed to wonder how he had managed it himself. So while the lunatic element made the journey down the ridge the rest of us went down to the beach and some of the chaps went for a dip. It was the perfect ending to a stunning day.

Words and images by Mark Barnes for War History Online. All material copyright: Mark Barnes 2014 unless stated. All Rights Reserved.