There are many well-known heroes of WWII. Oskar Schindler, who rescued over a thousand Jews from being sent to concentration camps by employing them in his factories. Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz who remained in the Nazi Army so he could advise Jews in Denmark about upcoming raids and Colonel Jose Arturo Castellanos Contreras of Salvador who, when stationed in Switzerland, saved thousands of Hungarian Jews by giving them phony Salvadorian visas.

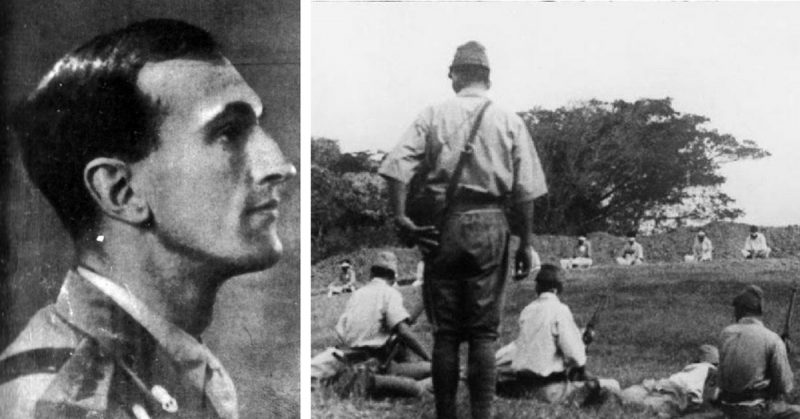

For all the heroes that became famous, there are just as many that did heroic deeds which, for them, was their duty. One of them, British Major Hugh Paul Seagrim, dedicated his life to resisting Japanese forces when they invaded Burma.

Seagrim was born in Hampshire, England in 1909. He was schooled at Norwich and then joined the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. In 1929 he obtained a commission in the British Indian army. He was sent to Burma and before long was accepted by the Karens, forming close friendships.

Burma, now called Myanmar, is situated west of Laos and Thailand in Southeast Asia. It was a colony of Great Britain from 1886 until 1948. The different major ethnic groups living in Myanmar are Burmans, Karen, Shan, Chinese, Mon, and Indian.

Most Indonesian countries regarded the British as haughty foreigners, who looked down on the native peoples while exploiting their land. They were pleased to find none of those traits in Seagrim.

He discarded his uniform, grew a beard and due to the sun his skin turned brown. The Major was always identifiable due to his extreme height of six feet four and earned the nickname “Grandfather Longlegs” from his men. He was a calm, grounded man who always put his men first and was kind to everyone.

In 1940, the Japanese invaded Burma, with their objective being the conquest of India. Over three hundred thousand British soldiers were forced to withdraw. Seagrim, however, stayed and fought.

The Burmans had their own Independent Army, which sided with the Japanese against the Karen, who possessed only crossbows for protection. Seagrim and his men hid in the jungle and obtained food and weapons when they could. Forced to move around to keep out of reach of the Japanese, they slept in crude bamboo huts and often had to eat rats. The Major was a man of faith and held a daily prayer service for those whose families had been converted to Christianity by missionaries in the 1800s.

After about a year of guerrilla warfare, the Japanese were aware of Seagrim and his men. Having by then lost their ability to wage war, they spied on the Japanese and relayed information to the British in India. Seagrim begged for reinforcements but to no avail.

The frustrated Japanese began attacking the Karen villages to flush the Major out of the jungle. One of their victims finally gave in after horrendous torture and revealed the location of the guerrilla army. As many as three hundred Japanese soldiers closed in on the area, but Seagrim and his men escaped.

Rather than put the Karens in any more danger, the Major decided to surrender. He was taken to the “Rangoon Ritz,” a notoriously brutal prison. All through his captivity, the Major kept his poise, good humor and ability to walk with his head held high. He pleaded for the lives of his men, pointing out that he was the spy, not the Karens. When Seagrim refused to do what the guards told him, he did so courteously. He would not bow or show any submission but did so without animosity. Just his presence buoyed the spirits of the other prisoners.

After being sentenced to death by a Japanese tribunal, and ordered to dig their own graves, Seagrim and seven of his men were executed on September 22, 1944, as they were singing a hymn.

Seagrim posthumously received the Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire; the Distinguished Service Order and the George Cross.

The medals are on display at the Imperial War Museum in London.