In April 2006 Peggy Harris of Vernon, Texas finally visited the village where her husband Billie died in July 1944. It had taken 62 years to find out what had happened to the young fighter pilot.

2nd Lt. Billie Dowe Harris and Peggy Seale were married on September 22, 1943. They began corresponding through the mail after Billie’s father, who worked with Peggy, recommended they meet each other. She was an electronic instrument mechanic at Altus Air Force Base, and Billie was stationed in San Antonio for flight training. They wrote each other for several months before meeting in person when he was 21, and she was 18. They were married in Florida while Billie went through advanced training before shipping out for the war.

Their two weeks leave for their honeymoon was cut short when a troop ship of pilots was torpedoed by the Germans. Billie was sent to Europe and assigned to the 355th Fighter Squadron/354th Fighter Group in October of 1943. The couple had only been married for six weeks.

Billie flew a P-51 Mustang on missions into German-held territory, supporting the big bombers as they lumbered into Germany to drop their payloads. After D-Day, his missions were direct attacks on ground targets in France. His flying earned him two Air Medals with 11 oak leaf clusters. He also earned the Distinguished Flying Cross.

During this time, Peggy knew very little of what her husband was doing in the war. The mail was censored, and Billie couldn’t tell her a lot of what was happening in his letters. Finally, in July 1944, he wrote to tell her that he had completed nearly 100 missions and they were sending him home. Wounded soldiers had priority, though, and he was forced to wait for the next ship home. The letter was dated July 8, 1944.

Later that month, Peggy received a telegram informing her that her husband had been killed in the line of duty on July 7, 1944. Peggy went to the telegraph office to see if the telegraph operator had made a mistake. She received a telegram from the war department correcting the date to July 17, 1944.

She later received notification that Billie had returned to the States on leave. No one in the family had heard from him, however. When she checked with the Red Cross to find out what had happened to her husband, she was told that he was most likely in a military hospital and would be released as soon as he had recovered.

In March 1945, having received no further word about Billie, she went back to the Red Cross who told her it was too expensive to investigate his whereabouts. She contacted her congressman who reached out to the International Red Cross. She then heard that Billie was missing, then heard that he was killed, and then that he was missing. No one she talked to seemed to know what had actually happened to her husband.

In 1948, she received paperwork to instruct the military as to where they should bury the remains of Billie. She didn’t believe they had his remains since no one knew where Billie was, but she signed the papers and, for the first time, was eligible to begin receiving military benefits.

Billie’s cousin, Alton Harvey, had heard the stories about Billie his whole life. When he retired, he decided to find out the truth about what happened to Billie. He spent a few years doing extensive research and learned that the military records of some pilots who had been buried in France were being made available to the public. He was told that it might take a long time to pull the records from the files but, a few days later, the records were ready. It turns out that someone in France had recently requested the same records.

That someone was a board member from Les Ventes, France. Her name is Valerie Quesnel. She was researching a Canadian pilot who had been shot down over their town. He managed to control his plane on the way down and crashed in a wooded area outside of town. His jacket had the name “Billie D Harris,” which the French assumed was “Billie D’Harris.” They, therefore, assumed he was Canadian.

The townspeople considered Billie a hero for fighting for their freedom. They gave him a hero’s burial and held a ceremony three times a year to celebrate the freedom fighters, soldiers and townspeople that sacrificed their lives for their small town. They celebrated on D-Day, on the day their village was liberated and on the day the war ended. Included in the ceremonial honors was the “Canadian” pilot, Billie Harris.

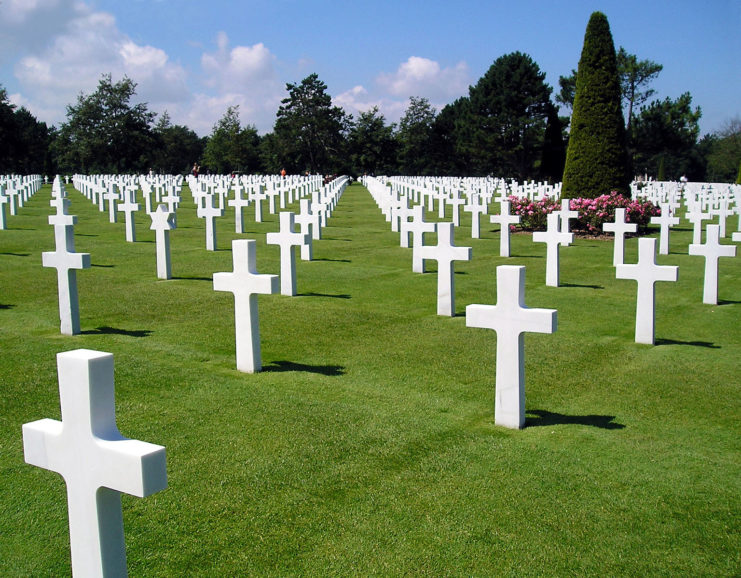

Eventually, Billie’s remains were moved to the Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-Sur-Mer. Quesnel confirmed that he was buried there and was listed as being an American airman. She began searching the US military records for information about the town’s hero with the intent of including that information in their 60th-anniversary celebration of their liberation.

When Harris received Billie’s records, they were marked, “killed in action.” There was also a record of how the Les Ventes people cared for Billie’s remains after he died. Quesnel’s name and contact information was also included in the records. Peggy wrote to Quesnel to thank her for her town’s treatment of her husband. The two women corresponded and shared what they knew about Billie.

Peggy has visited the town where they still have a memorial with her husband’s name on it, and they still honor him three times a year. She has received photographs of the original burial ceremony the town had for her husband. She has shared her own photographs of him with the town.

She is the last widow to still make the trip to the cemetery to remember her husband. In 70 years, she has not remarried. She says that Billie was married to her for the rest of his life and she has decided to be married to him for the rest of hers.

Peggy has gone on to live a full life. She got her degree in the humanities with a minor in philosophy. She has worked for a mining company, a savings and loan, she has had her writing published, and she has served as a librarian, among her many jobs.

In all that time, she remained faithful to the memory of her beloved husband little realizing that, half a world away, an entire town was doing the same.