In 1963, Warner Bros. released a film about the WWII sinking of JF Kennedy’s Patrol Torpedo (PT) boat. Called ‘PT 109’ the film was the first commercial movie about a serving American President.

Recently Producers Beau Flynn and Basil Iwanyk have teamed up to make ‘Mayday 109’, a film that will tell the real story of how Kennedy’s PT boat was sunk by a Japanese destroyer.

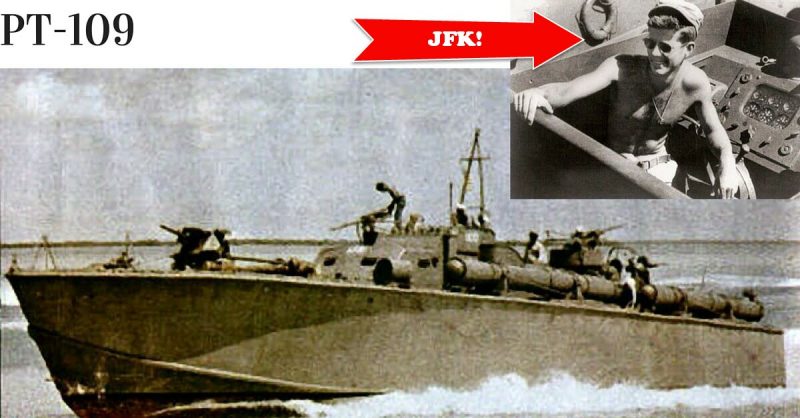

PT boats were small, fast attack boats armed with torpedoes. Powered by liquid cooled aircraft engines, these vessels could touch 45 miles per hour and although they were limited to coastal waters they were formidable in action – the Japanese Navy referred to them as ‘Devil boats’.

Born on 29th May 1917, John F. Kennedy desperately wanted to join the US navy. His wealthy, well- connected father pulled some strings, and in 1942 Jack (as he was known) volunteered for service with a PT boat unit in the pacific.

On the night of 2nd August 1943, the 40-ton PT boat 109 commanded by 26-year-old Lieutenant J.F. Kennedy was on patrol in the Solomon Islands in company with two other PT boats. Their mission was to patrol following intelligence reports that three Japanese destroyers were to run through the area that night.

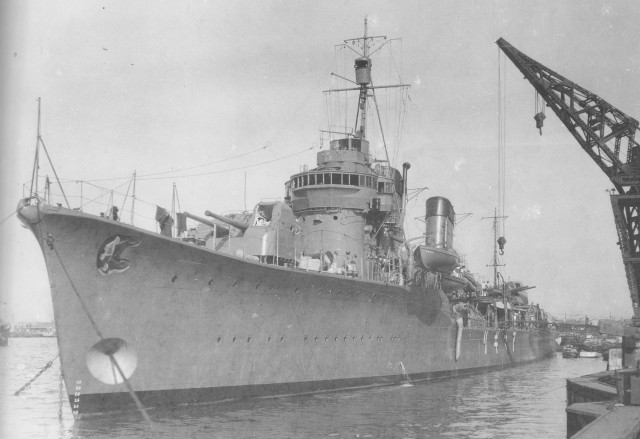

Around 2:00 a.m. on a moonless night, Kennedy’s boat was idling on one engine to avoid detection of her wake by Japanese aircraft when the crew realized they were in the path of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, which was returning to Rabaul. Amagiri was traveling at a relatively high speed of between 23 and 40 knots in order to reach harbor by dawn, when Allied air patrols were likely to appear.

The crew had less than ten seconds to get the engines up to speed, and were run down by the destroyer between Kolombangara and Ghizo Island.

Conflicting statements have been made as to whether the destroyer captain had spotted and steered towards the boat. Some reports suggest Amagiri ’s captain never realized what happened until after the fact. Damage to a propeller slowed the Japanese destroyer’s trip to her own home base.

PT-109 was cut in two. Seamen Andrew Jackson Kirksey and Harold W. Marney were killed, and two other members of the crew were badly injured. For such a catastrophic collision, explosion, and fire, it was a low loss rate compared to other boats that were hit by shell fire. PT-109 was gravely damaged, with watertight compartments keeping only the forward hull afloat in a sea of flames.

The eleven survivors clung to PT-109’s bow section as it drifted slowly south. By about 2:00 p.m. it was apparent that the hull was taking on water and would soon sink, so the men decided to abandon it and swim for land.

As there were Japanese camps on all the nearby large islands, they chose the tiny deserted Plum Pudding Island, southwest of Kolombangara. They placed their lantern, shoes, and non-swimmers on one of the timbers used as a gun mount and began kicking together to propel it. Kennedy, who had been on the Harvard University swim team, used a life jacket strap clenched between his teeth to tow his badly-burned senior enlisted machinist mate, MM1 Patrick McMahon.

It took four hours to reach their destination, 3.5 miles away, which they reached without interference by sharks or crocodiles.

They made it to the 100-yard-wide island, but there was no food or water. Kennedy swam in search of help, leading his men to nearby Olasana Island, which had coconut trees and water. Kennedy scratched a message on a coconut shell, and persuaded friendly natives to deliver it to an allied base at Rendova.

The explosion on 2 August was spotted by an Australian coastwatcher, Sub-lieutenant Arthur Reginald Evans, who manned a secret observation post at the top of the Mount Veve volcano on Kolombangara, where more than 10,000 Japanese troops were garrisoned below on the southeast portion.

The Navy and its squadron of PT boats held a memorial service for the crew of PT-109 after reports were made of the large explosion.

However, Evans dispatched islanders Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana in a dugout canoe to look for possible survivors after decoding news that the explosion he had witnessed was probably from the lost PT-109. They could avoid detection by Japanese ships and aircraft and, if spotted, would probably be taken for native fishermen.

Kennedy and his men survived for six days on coconuts before they were found by the scouts. Gasa and Kumana disobeyed an order by stopping by Naru to investigate a Japanese wreck, from which they salvaged fuel and food. They first fled by canoe from Kennedy, who to them was simply a shouting stranger. On the next island, they pointed their Tommy guns at the rest of the crew since the only light-skinned people they expected to find were Japanese and they were not familiar with either the language or the people.

The message was delivered at great risk through 40 miles of hostile waters patrolled by the Japanese to the nearest Allied base at Rendova. Later, a canoe returned for Kennedy, taking him to the coastwatcher to coordinate the rescue. PT-157, commanded by Lieutenant William Liebenow, was able to pick up the survivors.

Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his part in the escape and was later reunited with the coconut shell. He kept it on his Oval office desk throughout his presidency.