Pedro de Lara was bored. His had lived a full life, a life of personal pride and skill at arms, of politics, wine and of romance. At his peak, he had been the lover of Urraca, Queen of all Spain, and he had wielded influence at court, held great wealth and enjoyed every luxury that life could offer. Before that chapter in his life he had been the governor of several provinces, a largely pleasant and peaceful period, by the standards of the time.

In his youth, he had been on Crusade, where he had learned to enjoy the terrifying chaos of battle. He had been at the great siege of Antioch, where he had saved the Count of Flanders from certain death, fighting hand to hand beneath the walls in the scorching heat.

Now, he was in his early fifties, or thereabouts – he had lost count some time ago, and could not bring himself to care all that much. He knew that his body was old, still strong, but getting unsteady, and the weight of a lance or armour seemed greater than it used. Days in the saddle hurt immensely, though he carried it well. Even his eyes were dimming. No longer the dashing young nobleman who had wooed the hard-eyed, pragmatic Queen Urraca, and achieved power at her side.

She had been dead for more than a decade, and he missed her. Under her, the realm had been almost peaceful, kept in check by her power and her wise rule. After the death of the Queen several northern provinces rebelled, and the nobles took Pedro as their banner and their leader. The rebellion was quickly quashed, and Pedro and the others found themselves exiled and deprived of lands and titles.

Now, he was just an exiled knight, tagging along with army of the King of Aragon, hero of the Reconquista, the wars to re-take Spain from the Moors. De Lara was just another soldier at the siege. The King of Aragon was Alfonso I, called the Battler. His mission was conquest. In the quickly shifting quagmire of the politics of the day war was commonplace, and the Battler was always in conflict with somebody. In the year 1131 it was the Duke of Aquitaine, who was besieged in the walled city at Bayonne with five thousand men.

Alfonso’s army was well established around the walls. In the early stages of the siege the surrounding areas had been raided and assaults had been attempted against the walls, but by the time summer of 1131 rolled round all had been quiet for a long time, and Pedro was bitter, morose and very, very bored.

There was a stir in the camp. A messenger had arrived with news of a relief army arriving to aid the besiegers. They were coming, they would be here soon! Who led them? Alfonso Jordan, Count of Toulouse! Pedro felt the knife of dull anger and frustrated ambition twist in his belly at the sound of the name. Alfonso Jordan, Count of Toulouse, the man who represented everything Pedro should have been, everything he had failed to keep a hold of.

They had history, these two. Through the days of the Crusade, through the days as Count and the days with the Queen, Pedro had observed Alfonso Jordan from a distance. Jordan had been on the right side in the turmoil which followed the death of the Queen, and while Pedro was now little better than a high-end mercenary, Jordan was a landed nobleman, wealthy and renowned, and high in the esteem of Alfonso the Battler.

Jordan and his relief troops arrived with great pomp and splendour in the late morning. It was hot, dry and very still, and Pedro observed him through a haze of rising fury. Jordan’s arrogance, his ostentatious clothing, his lordly, condescending bearing. All of Pedro’s frustration and boredom focussed like the point of a lance on the smiling face and loud voice of the new arrival. Slowly, the thought formed in Pedro’s mind. I’ll kill him. I’ll challenge him to single combat and I’ll kill him. He found himself smiling.

Jordan was insulted. He had not recognised the sweaty, grimy, heavyset knight who approached him, roaring out his challenge. When he asked the man at his side and heard the name, his first thought was ‘how far and how fast one man can fall.’ He had thought de Lara fled or dead, and little expected to find him here, still warring in the northern provinces of Iberia. He did not speak to Pedro directly, but ordered his squire to tell the old knight that the challenge was accepted.

They set up the joust on a wide, hard plain midway between the besieging army’s camp and the city wall. It was the most exciting thing that had happened in many months, and a festival atmosphere prevailed as men gathered to see the show.

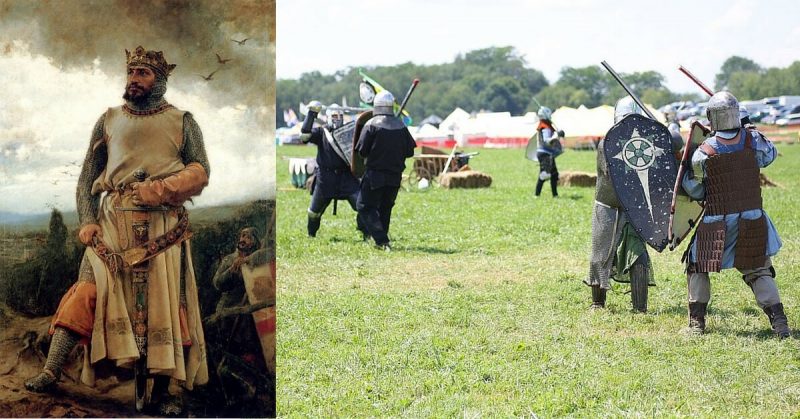

At this early time, a joust meant something quite different from the stylized and chivalrous contest it would become in later centuries. This was not tilting over lists to unhorse an opponent, it was a duel to the death, single combat beginning with the lance but not governed by any rule beyond that. The armor was not the ornate plate of later times, but heavy, functional layers of chain mail and boiled leather.

Their horses were unarmored and unadorned. Even on the walls of the besieged city, little figures could be seen gathering to watch the contest.

Pedro and Alfonso Jordan faced each other across the long sweep of dusty ground. A squire blew a loud blast on a horn, and they began to thunder toward each other. They reached a furious momentum, and the last moment Pedro tried to twist his body around and hit Alfonso in the face with his lance, but too late. Alfonso’s lance connected with Pedro’s chest and he flew from the saddle and sailed through the air, landing badly.

He was stunned, the wind knocked out of him, and Alfonso was out of the saddle in the blink of an eye. In his hand he held a huge mace of black iron with a barbed head. He threw aside his shield and raised the mace with both hands, rushing toward the gasping figure on the ground. Pedro rolled to one side at the last moment, and the mace thudded into the earth. Up on one knee, he raised his round shield against Alfonso’s next swing. The shield shattered, and he was dully aware of his left forearm breaking under the force of the blow. He went forward and up, sword in hand, and barged his left shoulder into his enemy’s midriff.

Alfonso staggered back a step and Pedro swung his sword up, but suddenly Alfonso stepped in under his guard. A long dagger flashed in his gloved hand. It dipped in and out, and then the mace struck a ringing blow on the side of Pedro’s great helm. Pedro de Lara fell and did not rise again.

They carried him away to a tent in the camp where an old monk tended him for the two days it took him to die. Pedro did not speak again, and when he finally stopped breathing they took him and buried him nearby with little ceremony. So ended the career of a man who had once been known as the most influential man in the court of the Queen of Spain.

-by Barney Higgins