In the early 14th century, the Japanese Emperor Go-Daigo raised an army. He sought to do what his predecessors had failed to – take control of the country he ruled.

After the Mongols

For much of feudal Japanese history, the country was not run by the emperor. He was a mere figurehead. The actual ruler was the shogun, a military warlord, or sometimes a regent using the shogun as a puppet.

During the 1270s and 1280s, the forces of the Hojo regency defeated a series of attempted invasions by the Mongols. Rewarding lords and monks for their part in the success drained the coffers of the shogunate government. The Hojo had been weakened.

The time was ripe for an emperor to retake control.

Go-Daigo Prepares for Power

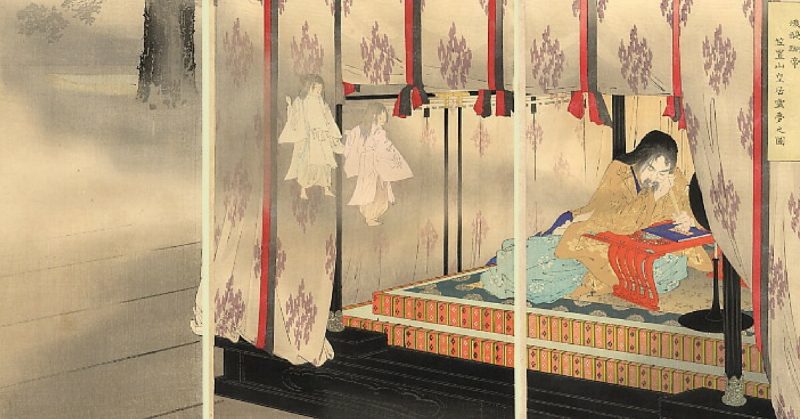

In 1318, the Emperor Go-Daigo attained the throne. He immediately started preparing to take control of his empire.

Until 1321, emperors were too busy with ceremonies to do the real work of politics. Instead, an emperor would abdicate, making his son a figurehead emperor while he ruled. Go-Daigo ended the tradition of the Cloistered Emperor.

With more than half of the feudal lords connected to the Hojo, Go-Daigo turned to the monasteries for support. He sent his son, Prince Morinaga, to be a monk at Mount Hiei, home to many of the warrior monks known as sohei. In 1328, he promoted Morinaga to Abbot of Mount Hiei. Go-Daigo also made generous gifts to the monasteries of Nara.

The Flight to Nara

In September 1331, the Hojo learned that Go-Daigo was plotting against them.

Before they could strike at him, Go-Daigo fled to safety in Nara. He took with him the imperial regalia, which consisted of a mirror, a sword, and a set of jewels. The monks there feared their position was not strong enough to hold out against an attack. He moved to Mount Kasagi, another home of the warrior monks.

Isolated and Deposed

The Hojo clan moved to isolate Go-Daigo both militarily and politically.

Politically, they tried to force him to abdicate. When he refused, they announced he was deposed and declared a new emperor.

Militarily, they focused their forces on Mount Hiei. Prince Morinaga was compelled to flee. Go-Daigo was left isolated at Kasagi.

The Fight for Akasaka

Morinaga moved to a fortified encampment called Akasaka. There he joined the forces of a samurai named Kusunoki Masashige.

Kusunoki came from an obscure warrior family. It was his skill as a leader and his loyalty to the emperor that propelled him to fame during the war. Together, he and the Prince led the forces holding out in Akasaka against a determined attack by Hojo forces.

Outnumbered and isolated, it became apparent the fortress would fall. Rather than fight to the last and then commit suicide, as was often the samurai way, Morinaga and Kusunoki fled to fight another day.

Go-Daigo’s Fall

Meanwhile, things had gone badly for Go-Daigo.

He had tried to join his son but was captured on the way by Hojo forces, who took him to their headquarters in Kyoto. From there, he was exiled to the island of Oki in early 1332.

It appeared the revolt was over.

Rebuilding Resistance

However, Go-Daigo’s supporters were made of stronger stuff. Morinaga and Kusunoki were determined to keep the fight alive.

Prince Morinaga moved to Yoshino, a mountainous district where he could use the terrain to his advantage. He gathered a force of warrior monks around him, using his fame and his previous connection with the holy orders. From his new base, he reached out to those samurai clans who might support him, calling for their help.

Meanwhile, Kusunoki returned to Akasaka. There he built a new stronghold, Kami-Akasaka. Higher up the mountain, it was harder for the enemy to attack and he inflicted heavy losses on them.

Frustrated at the continued resistance, the Hojo rescinded orders for the two leaders to be taken alive. Instead, they were to be executed.

In early 1333, three armies set out to crush the rebels.

The Siege of ChihayaAt first, their campaign went well. Both Yoshino and Kami-Akasaka fell, but neither the Prince nor Kusunoki were captured.

Kusunoki retreated to a stronger fortified base at Chihaya. There the Hojo forces were brought to a halt. Faced with the unfamiliar and mountainous terrain, they were unable to overcome the defenders. Kusunoki’s forces lured them into ambushes, rolled boulders onto them from cliff edges, and dug pit traps to slow their advance.

This time, the rebel fortress held out.

Go-Daigo Returns

The example of Chihaya inspired other samurai clans. They saw that the Hojo could successfully be opposed. It also inspired Go-Daigo. In the spring of 1333, he escaped from Oki and went to Hoki Province rallying troops to fight for him once more.

Two armies were sent to attack Go-Daigo. One was quickly destroyed, defeated by a guerrilla army. The remaining Hojo force was under the command of Ashikaga Takauji.

Takauji came from a prominent family. He realized that gave him the status he needed to become a shogun if a grateful emperor should choose to give him the position. He defected to Go-Daigo’s side.

Takauji captured an important headquarters at Kyoto. Go-Daigo, still in possession of the imperial regalia, rode into the city in triumph. He made the substitute emperor abdicate and retook the throne himself.

Kamakura Falls

The remains of the Hojo forces retreated to their base at Kamakura. Opportunistic samurai clans gathered and descended upon the city in the emperor’s name. After five days of fierce fighting, the last Hojo regent and his remaining men retreated to a Buddhist temple. There they committed suicide while the city burned around them.

For the first time in many years, the Japanese Emperor ruled his country.

Source:

Stephen Turnbull (1987), Samurai Warriors;