“Crucible: Life & Death in 1918” Opens Tuesday, April 3

The word “crucible” is defined as: a situation of severe trial, or in which different elements interact, leading to the creation of something new.

1918 was a tough year. American land forces forged their fighting force in regions across the world. The global war provided American women with unforeseen opportunities to serve their country in uniform. The Allied forces and Central Powers clashed in unprecedented conflicts leading to an Armistice on Nov. 18, 1918. The stable world of the aristocrats and monarchs vaporized. Empires collapsed. New powers emerged.

Crucible: Life & Death in 1918, a new special exhibition opening on Tuesday, April 3 in Exhibit Hall at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, shares the incredible stories of the individuals whose lives were caught in this extraordinary crucible in 1918.

“In recent history, one would be hard-pressed to identify a singular year with greater turmoil and upheaval with long-lasting consequences than 1918,” said National WWI Museum and Memorial Senior Curator Doran Cart. “Trying to make sense of this incredibly tumultuous period of time is challenging and through Crucible: Life & Death in 1918, we share how the world changed forever through highly personal stories of the people who lived through it.”

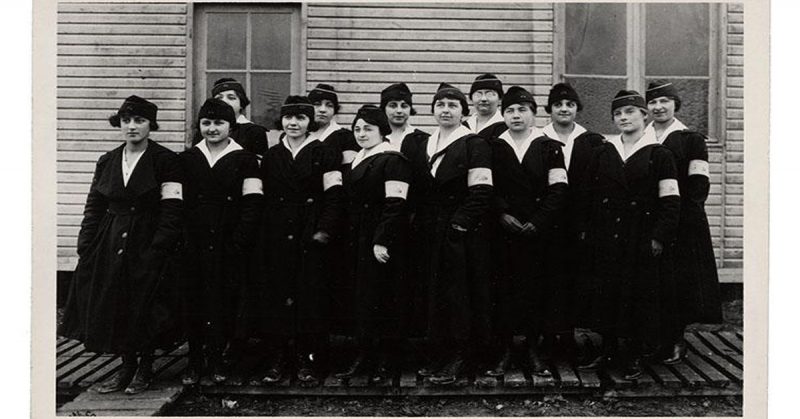

One such individual is Grace Banker, Chief Operator of the U.S. Signal Corps’ women telephone operators. Women telephone operators were recruited for their civilian experiences and ability to speak French. Banker, whose service tunic is on public exhibition for the first time along with other personal items, received the Distinguished Service Medal and later wrote:

“The work was fascinating; much of it was in codes changed frequently. ‘Ligny’ was ‘waterfall.’ ‘Toul’ might be ‘Podunk’ one day and ‘Wabash’ the next. Once in a mad rush of work I heard one of the girls say desperately, can’t I get ‘Uncle’ and another no I didn’t get ‘Jam.’ The girls had to speak both French and English and they also had to understand American Doughboy French.”

The women were often in range of German artillery, but they stayed at their posts because their work was essential. After the war, Banker and the other female telephone operators were treated as volunteers and discharged without proper veteran’s status. It wasn’t until 1977, long after her death in 1960, that this was rectified by legislation and the surviving telephone operators received full recognition and benefits.

For the Doughboys on the Western Front, 1918 was their year. They fought alongside their main allies: the British Empire, French, Italians, Czechs and the White Russians from Cantigny to Belleau Wood to the Champagne Region, the Piave River to the Marne to St. Mihiel to the Meuse Argonne to Vladivostok.

The Western Front American forces encountered scenes of environmental degradation, obliterated villages, vast cemeteries, and continuing massive destruction. Much of the landscape of the Western Front looked like an uninhabited planet very foreign to them.

The British and French generals wanted the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) Commander, General John J. Pershing, to integrate U.S. units into their armies. Instead, Pershing insisted on a separate American army.

At an Allied conference in May 1918, when Allied lines were near breaking, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch demanded, “Are you willing to risk our being driven back to the Loire?” “Yes, I am willing to take the risk,” Pershing replied. “The time may come when the American Army will have to stand the brunt of this war, and it is not wise to fritter away our resources in this manner.”

Except for a few units detached to help stop the German advance in the spring of 1918 and a few other occasions, the AEF fought as an American force under Pershing’s direct command.

1918 was by no means solely an American show as the Allies still shouldered the lion’s share of the action. In the aftermath of the Armistice, major swaths of the world appeared scarcely familiar. The German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman Turkish, and Russian empires all collapsed. Bolshevism took over Russia. Japan’s power in Asia and the Pacific grew. China descended into civil war. Arab nations seethed for independence. Under British rule, Jewish settlement expanded in Palestine. The United States’ position in the world drastically changed as well.

Crucible: Life & Death in 1918 is open from April 3, 2018 through March 10, 2019 and is included with a general admission ticket to the Museum and Memorial.