It was a cool, and calm evening, on April 22, 1915, on the Gravenstafel Ridge Northeast of the town of Ypres, France. Soldiers of the 13th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force sought what little comfort they could find. There was no artillery that evening, sentries had been posted, and the two French divisions on their right flank ensured their security. If the Germans wanted to attack, they were ready.

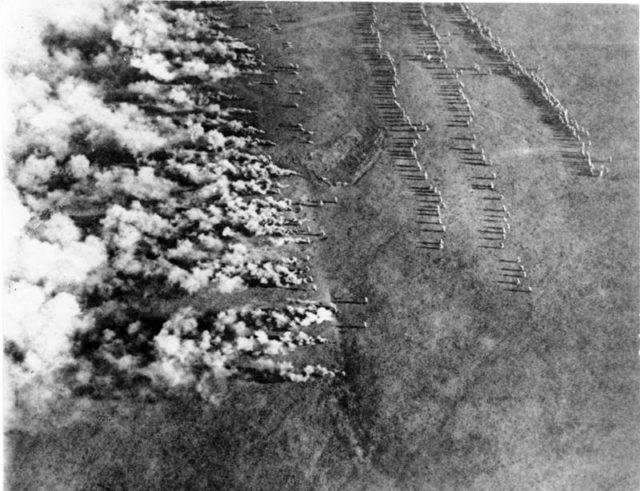

Little did they know but across no man’s land, the Germans were busy. For the past week, 1000’s of 90 lb canisters had been carried, by hand, to the forward trenches. At night, hoses had been brought into no man’s land, where they sat, ready for use.

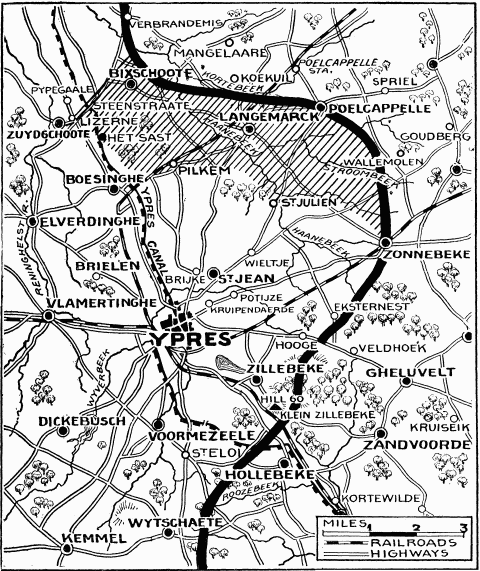

By the 22nd everything was in place, and German Pioneers stood ready to unleash their deadly power. At 5 pm, a massive cloud enveloped 3 miles of ground, stretching from Langemark, to Steenstraat. French officers reported a smoke cloud, covering a German assault. Whistles, yells, and orders filled the air as Algerian and Moroccan troops were rushed to the front, to fend off the inevitable infantry charge.

The soldiers reported an odd smell, as the greenish-yellow haze moved towards them, pushed by a gentle spring breeze. As it neared their trenches, troops felt their lungs begin to burn. Every inhalation felt like scalding steam, and their eyes streamed with tears as the stinging fumes enveloped them. It was chlorine gas.

The French troops were defenseless against it. The Hague Convention had outlawed chemical weapons, so European armies had not issued gas masks to their soldiers. Terrified, the French soldiers tried to flee. Chaos ensued. Officers and men alike succumbed to the gas, as 6,000 fell victim in a matter of minutes. As men clambered to get out of their trenches, where the gas had settled, German gunfire picked them off causing, even more, panic and fear.

Canadian forces to the southeast watched in horror as their allies suffered. They had no idea what was happening but could see thousands of French troops running for their lives, and that their flank had been exposed. When they realized it was a gas attack, the Canadians held back, avoiding the poison filled trenches. They watched as German troops marched forward, unopposed, across no man’s land. They became surrounded on three sides, a peninsula in a sea of enemies.

The Canadians had a solution. By urinating into a rag, and tying it over their mouth and nose, they prevented asphyxiation. They used goggles over their eyes to protect them. Then they cautiously pushed forward, hoping to stem the enemy attack. The Germans, wanting to stay clear of the gas, advanced slowly. The Canadian troops opened fire on their enemy, but their attempt was too little, too late, as the Germans continued to move toward them.

For the next six hours, the beleaguered Canadians held the line, while a counter attack was organized. The 10th Battalion, 2nd Canadian Brigade, and the 16 Battalion (Canadian Scottish) of the 3rd Brigade, each with around 800 men, were formed and ready. Their orders were simple: drive the Germans out of Kitchener’s Woods, then retake the line and await reinforcements.

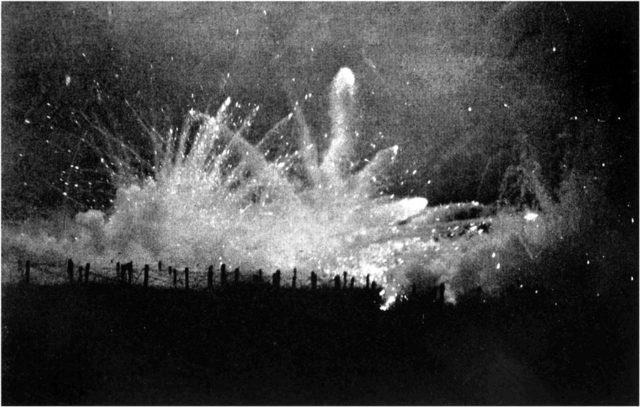

In the pitch black darkness of night, the men advanced into the unknown. There was no time for reconnaissance as the Canadians moved forward. The 10th Battalion made the first push, sending 400 soldiers to capture a hedgerow, 200 yards from the wood. When the troops arrived at the hedge, they found barbed wire had been woven in amongst the branches and twigs.

There was no time to remove it and make a proper path. The men smashed through using their rifle butts, boots, and bayonets to make holes large enough for their comrades. As they stumbled through to the other side, German machine guns opened up from the edge of the wood. Bullets ripped through the hedge, and the first wave of men was cut to shreds. The Canadians returned fire, covering an all out charge by the remainder of both battalions.

Sprinting over 200 yards, the troops dove into the woods, searching in the darkness for their hidden foe. The battle became a vicious hand to hand conflict as the Canadians pushed forward foot by foot, driving the Germans back. It was the first time that Canadian troops had seen any significant action in the war, but they earned a reputation for ferocious bravery against the odds.

With bayonet, boot, and club the 10th and 16 battalions proceeded further into the woods, losing many of their men along the way. French Colonial troops joined them, hoping to reclaim not only their honor but many of the machine guns and artillery pieces lost when the Germans had broken through, hours earlier.

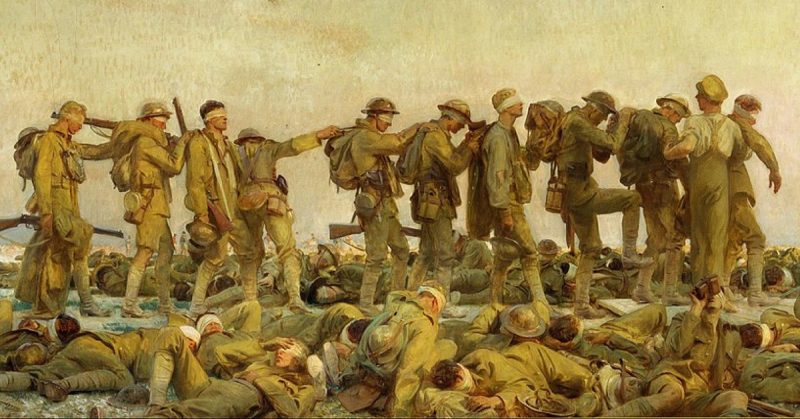

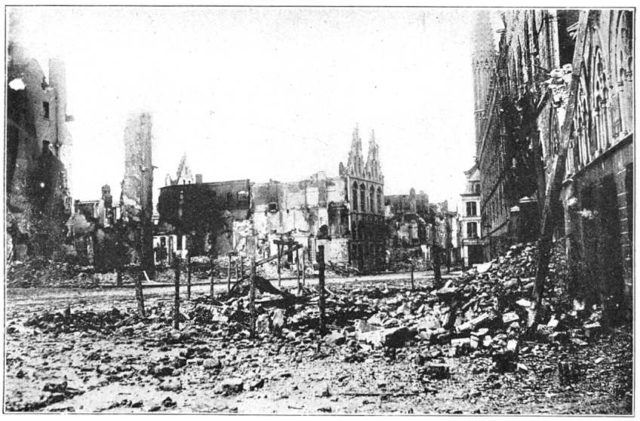

By dawn on the 23rd, the woods were in Canadian hands, and French troops marched back into their trenches. Behind them, they left a forest of bodies. The Canadian forces sustained between 60% and 75% casualties, with over 1,000 men killed. Bloodied, weary, and weakened, they held the line. However, the 2nd battle of Ypres was not over. In the following days, the Germans continued to use gas attacks at St. Julien and did not give up until the end of May.

The world took notice, though, of the Canadians at Kitchener’s Wood. The sparsely populated colonial dominion showed the world their bravery. Over the remaining war years, they proved it time and again as Canadian soldiers earned a reputation as relentless shock troops. After the war, French Marshall Ferdinand Foch called the attack on Kitchener’s Wood, “the greatest act of the war.”