When looking back at the Revolutionary War, many people immediately jump to two conclusions. First, is the popular misconception that the war was exclusively an American conflict, or a struggle waged entirely in North America. Second, is the tendency to conjure up images of colorfully-coated soldiers, rhythmically marching to flutes, who statically unleashed fusillades of musket and cannon fire upon one another.

While there are some wisps of truth to these statements, the Revolutionary War was, in all reality, a devastating global conflict brutally fought under a variety of terrible conditions.

This article represents the first effort, in a series of regular installments, aimed at dispelling a few of the above misunderstandings. The following feature and subsequent offerings will highlight some of the major battles and engagements that shaped the course of the Revolutionary War and America’s battle for independence.

The overall intention of this series is to provide readers a thematic representation of the past by recalling events conveniently collated into accessible snippets tied to months of the year. Some stories will be familiar. Others might be new. Either way, I hope to entertain and inform those interested in the harsh reality and true history of the Revolutionary War.

Without further delay, let us first look at the month of May and focus our attention on the myriad military actions that took place in continental North America and the Caribbean Islands. At first glance, the month appears nearly like any other of the war, filled with conventional engagements, backwoods skirmishes, and brutal sieges. Upon closer examination, however, it’s clear that the Crown did not fare well during the month of May.

From 1775 – 1782, over 20 significant engagements took place during May, with British forces conceding to their American or European adversaries on more than half those occasions. The fights that the British did win were either Pyrrhic victories or of little strategic significance in the grand scheme of the war. Ultimately, it was a miserable and moribund month for Great Britain and her allies. Below is a small sampling of the many conflicts that contributed to the decline of British power in the North America

The Patriot Capture of Fort Ticonderoga (May 10, 1775)

Although the British, under General John Burgoyne, famously dealt American forces an embarrassing blow with the successful siege of Fort Ticonderoga during the summer of 1777, it was the Patriot militia who struck the first upset two years earlier, in 1775. Partisans Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold, along with a small force of New England militiamen (called the Green Mountain Boys), captured the fort, its British occupants, and their cannons in a single stroke. There was little violence and the engagement itself was relatively uneventful. The capturing of Ticonderoga, however, provided Patriot forces with some much-needed artillery, stymied British communications, and gave the Continental Army a great boost in morale.

Battle of Hog Island (May 27 – 28, 1775)

Fought on Chelsea Creek, within the vicinity of Boston Harbor, the Battle of Hog Island was waged between a Patriot force of several hundred men and a slightly smaller contingent of British Royal Marines. Over the course of two days, American forces, under the command of John Stock and Israel Putnam, repelled a British amphibious raid that resulted in the capture of HMS Diana—a royal warship and the first vessel destroyed by Patriot forces during the Revolutionary War. American rebels, emboldened by the victory, later participated in the successful Siege of Boston.

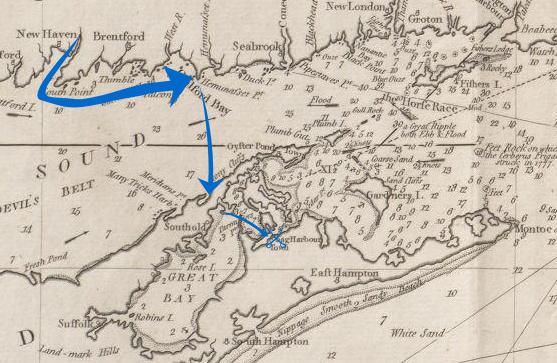

The Battle of Sag Harbor (May 24, 1777)

By the spring of 1777, it appeared a forgone conclusion that the British were going to win the war. They were in undisputable control of North America and on the verge of crushing the Continental uprising. British regulars, under the command of General William Howe, held New York firmly in their grasp.

Seemingly out of nowhere, American Colonel R. J. Meigs mounted a raid that shocked the British. In a bold nighttime attack, Meigs led an assault on Sag Harbor that culminated in the destruction of a dozen British boats and the capture of 90 prisoners. His actions proved that the British weren’t unstoppable and gave American revolutionaries the spirit to continue fighting.

Battle of Crooked Billet (May 1, 1778)

The Battle of Crooked Billet, fought about 50 miles north of Philadelphia, resulted in a British victory that, while of tactical significance, highlighted serious faults with the Crown’s overall military strategy. British generals John Graves Simcoe and Robert Abercromby, along with 850 men, surprised and eventually crushed an outnumbered and undersupplied contingent of American militiamen near Crooked Billet Tavern. The British killed two dozen Patriots, captured nearly twice that number, and destroyed vital supplies. Widespread reports of atrocities fueled American resentment, however, and the engagement proved that Patriot irregulars could stall and delay overwhelming British forces.

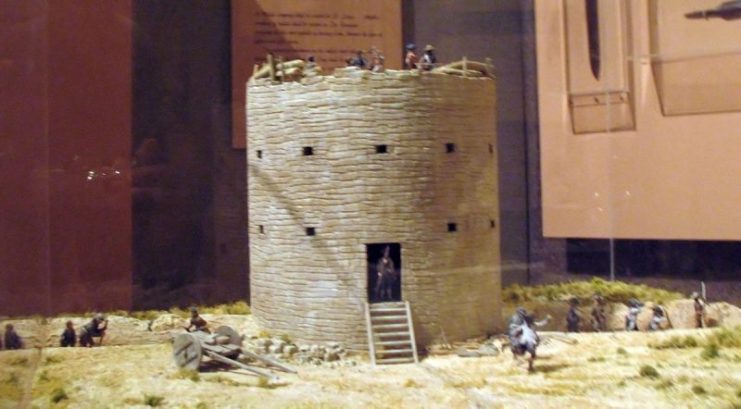

Battle of St. Louis (May 25, 1780)

The Battle of St. Louis, or the Battle of Fort San Carlos, was one of several Patriot-Spanish victories of the Revolutionary War. The fight took place in Spanish Louisiana around present-day Missouri. The British, in a bid to gain control of the Mississippi River, launched a joint Anglo-Indian assault on the village of St. Louis that, at the time, was under control of Spanish governor and army captain Fernando de Leyba. Three hundred Spanish-Patriots managed to hold off a superior force of over 1,000 Brits, Chippewas, and Sioux.

Historians credit the Spanish victory to a hastily erected series of fortifications and lead-ball ammunition, provided by the French-Canadian François Vallé. The lead musket balls afforded the Spanish-Patriots a distinct advantage over the British-Indian invaders who, after enduring a prolong expedition, were reduced to using stones and pebbles in their muskets.

Battle of Waxhaws (May 29, 1780)

From an American perspective, the Battle of Waxhaws was one of the most infamous engagements of the Revolutionary War. Although the fight resulted in a British victory, alleged atrocities committed by British Dragoon commander Banastre “Bloody Ban” Tarleton ultimately did more harm than good. The purported killing of surrendering American rebels stoked the fires of Patriot resentment through the conclusion of the war. Fought in the hills of South Carolina, the battle was one of the opening engagements of Great Britain’s Southern Campaign, following the capture of Savannah and Charleston in 1780.

The fight was a complete massacre, with Tarleton’s men killing or seriously wounding more than 150 American militiamen. The darkest part of the battle supposedly occurred near the end of the engagement when Tarleton’s cavalry cutdown surrendering Patriot troops. Tarleton insisted that he never saw the American flag of surrender, but southern militias still wanted to extract their revenge. The act gave rise to the phrase “Tarleton’s quarter,” which is what angry rebels shouted in subsequent engagements while mercilessly ambushing and killing British troops.

Siege of Augusta (May 26 – June 6, 1781)

The Siege of Augusta was an effort to reclaim the captured Georgia city from British hands and involved three pivotal figures of the Revolutionary War. Over the course of 11 days, American General Andrew Pickens, Colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, and Elijah Clarke compelled British Loyalist Thomas “Burnfoot” Brown to surrender the arrested town back to American forces.

The British surrender occurred in three phases. First, was the capitulation of 126 British regulars at a stockade house on May 21. Two days later, was the storming of Fort Grierson, where enraged Patriot forces slaughtered the garrison’s fleeing commander. Finally, was the Loyalist Thomas Brown’s surrender at Fort Cornwallis, which signaled the downfall of British influence in Augusta.

Invasion of Tobago (May 24 – June 2, 1781)

France had been invested in the Revolutionary War since 1778 and the assault on the British island of Tobago was one of several engagements in which French forces unilaterally acted against Anglo occupiers in the Western Hemisphere. The battle was huge, involving over 5,000 men and 30 ships of the line. In a nutshell, French Admiral Comte de Grasse gained control of significant parts of the West Indies by overpowering and outmaneuvering British forces in the Caribbean Islands.

An interesting aspect of the conflict involved de Grasse’s dispatching of French ships and troops to St. Lucia, which diverted British attention away from his main objective of Tobago. Great Britain’s military losses were relatively minimal over the duration of this conflict, but the forfeiture of valuable sugar and cotton plantations crippled the Crown’s war efforts abroad.

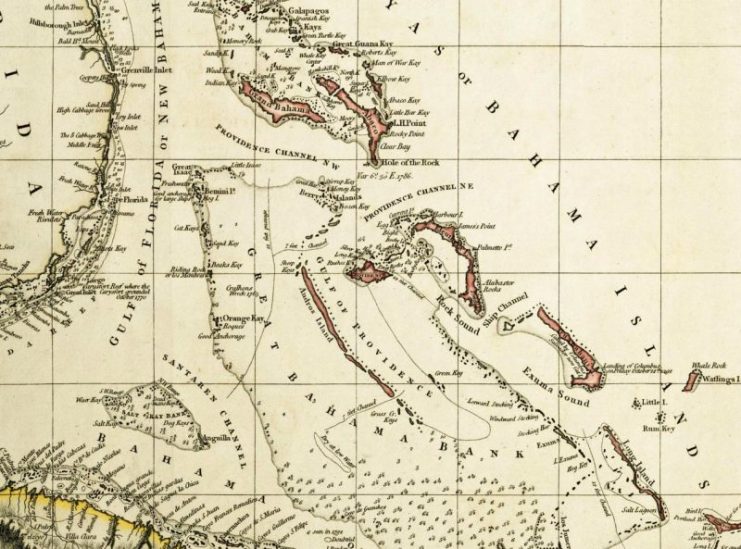

Capture of the Bahamas (May 6, 1782)

In the year following Great Britain’s loss of Tobago to France, Spanish forces wreaked additional havoc in the Caribbean by striking the Bahamas on May 6, 1782. British Admiral John Maxwell surrendered Nassau to the Juan Manuel de Cagigal without firing a single shot, which was hardly a surprising outcome. Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown the previous October, capitulating to Continental Army General George Washington and French expeditionary commander Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau, and the antiwar sentiment in Great Britain had reached its boiling point.

American and British delegates reached an initial peace agreement roughly six months later. The formal and final signing of the Treaty of Paris took place during the following year, in the winter of 1783. The Capture of the Bahamas, in addition to being yet another dismal May failure, was quite literally one of the final nails in the coffin of the Crown’s war effort in the Western Hemisphere.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Robert Ranstadler is a retired U.S. Marine and independent military historian who turned to freelance writing and editing after retiring from active duty service in 2015. He holds an advanced degree history, has written multiple feature-length articles, and is currently preparing a monograph about irregular tactics and partisan warfighters in the Revolutionary War. Robert resides in Virginia where he and his family enjoy hiking and exploring historic battlefields across the Southeastern United States.