“Brains! I don’t believe in brains.” – Prince George, Duke of Cambridge and Commander-in-Chief of the British army until 1895.

The “Peter Principle”, where people are promoted until they are proved incompetent, is infamous in management. While less discussed in the military, such promotions are disastrous there, costing thousands of lives and the fate of nations. In the 19th century, this became a particularly large problem, thanks to growing armies combined with nepotism and the ever-accelerating rate of change in warfare.

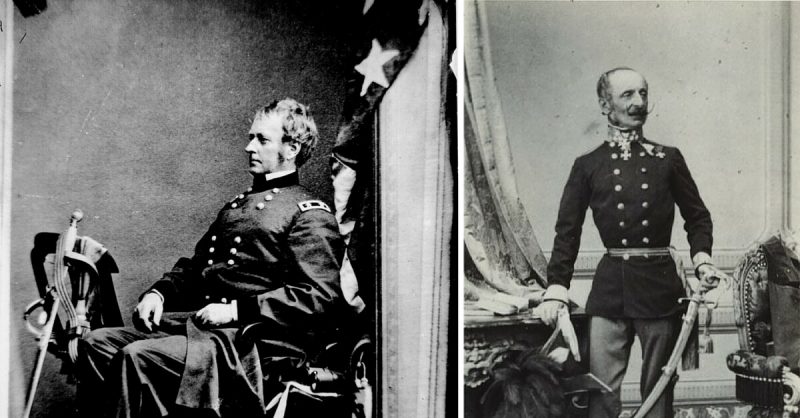

Here are some of the men who exemplified over-promotion.

Joseph Hooker

“My plans are perfect.” – General Joseph Hooker, before losing at Chancellorsville

Though he proved capable at other times in the war, General Hooker’s promotion to command of the Union Army of the Potomac proved disastrous for the men serving under him.

Hooker developed a plan of campaign that was elegant on paper but ineffective in practice. Brigadier General Stoneman’s cavalry raid, a vital part of the plan, was not pursued with the necessary vigour. An initially successful flanking march was countered by Stonewall Jackson.

Losing his nerve, Hooker retreated to Chancellorsville, where the far bolder General Lee outmanoeuvred him. Badly shaken by a close encounter with a cannon ball, Hooker refused to hand over command to other men, even as his command decisions deteriorated. Chancellorsville was a disaster for the Union, defeated by an army less than half the size of theirs. Hooker lost command of the Army of the Potomac but remained a general throughout the war.

Redvers Buller

Sir Redvers Buller was one of the greatest colonels in the British Victorian Army. An inspiring officer full of courage and daring, he won the Victoria Cross, his nation’s highest honour, for service in the Zulu Wars.

Unfortunately for Buller, he was promoted for his efforts, returning to South Africa as a general in the Second Boer War.

Buller had already shown his poor sense of priorities. During training manoeuvres, he refused to continue past 5 pm so as not to affect his officers’ social lives and ordered men not to damage their uniforms by diving into cover. In the face of the Boers, it became clear that he also lacked tactical acumen or the ability to manage other generals. Men became lost on marches. Hundreds were left behind after not being told about a retreat. None of the lessons of the First Boer War were put into practice, as Buller tried to maintain a traditional style of gentlemanly warfare against a far more pragmatic opponent.

The campaign was such a fiasco that he earned himself the nickname Sir Reverse Buller.

Ludwig von Benedek

An Austrian of Hungarian descent, Ludwig Benedek graduated seventh in his class from the Theresiana Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt. He proved his talents when commanding Austrian troops in Italy, rising from lieutenant to Major General, was made a Knight (adding “von” to his name) and was awarded several medals.

When war broke out with Prussia in 1866, Benedek was made commander of the Austrian Northern Army. At that point, his most notable achievement had been a successful retreat in the face of the French seven years earlier. An actual victory was to prove beyond his capability as a general.

To Benedek’s credit, he knew that he was not the man for the job. He had previously turned the command down several times, on the basis that he knew neither the enemy nor the region he would be fighting in. But in his nation’s hour of need, he reluctantly took command against Europe’s fastest rising military power.

Benedek went on the defensive, giving the Prussians time to take out Austria’s allies – Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, and Saxony. Several months into the war, he finally ordered his troops into the field, only for them to suffer a string of defeats. Unable to amass his strength, he was severely shaken, and his pessimism spread through the army, damaging morale. Facing the Prussians in the decisive Battle of Königgrätz on 3 July, he was defeated by a numerically inferior force. The Austrians were driven into retreat, and signed an armistice 18 days later, surrendering much of their power on the continent.

Achille Bazaine

Benedek was not the only officer whose weakness was exposed in the face of the Prussians. François Achille Bazaine had risen from the rank of Fusilier to Marshal of France in a career marked by calm under fire and leadership from the front. Sadly these qualities did not make a strategically minded commander, or in Bazaine’s case one his country could depend upon.

During the Franco-Prussian War, Bazaine and the forces he commanded became surrounded at Metz. Unable to break through the encircling Prussians, and without the ability to find an innovative solution, Bazaine instead negotiated with the enemy.

He had already refused to obey the new French government due to his Bonapartist politics, and rather than cooperate with his political opponents he surrendered 180,000 French soldiers to the invaders. As with so many over-promoted commanders, courage had not been enough to bring him victory.

The Duke of Cambridge

Prince George, the Duke of Cambridge and a cousin of Queen Victoria, was commander-in-chief of the British army from 1856 until 1895. Elderly and conservative to the point of incompetence, the Duke opposed reform in an era when wars in Europe and America were proving the importance of modern technology.

Such was the Duke of Cambridge’s resistance to change that he showed hostility toward any officer who took the terrible step of studying the art of command. Thanks to his influence, by the end of the century 50 times as much military literature was written in German as it was in English, leaving Britain’s army at an intellectual disadvantage. But with his royal blood and powerful connections, no-one was going to remove the Duke from his post.