In creating gunpowder weapons, European engineers took a Chinese innovation and made a deadly weapon of war. From the start, this was as much about heavy artillery as handheld guns. That artillery has changed dramatically over the years.

14th Century Guns

Some of the first records of gunpowder artillery are found in the 14th century, and as far from China as they could practically get – in the hands of English armies. An English manuscript of 1327 shows an early depiction of artillery, which would then see use on the battlefields of the Hundred Years War. Crécy (1346) may have been decided but archers, but it was remembered by many participants as they day they first heard the canon’s roar.

Charles VIII

Hard to move due to their weight and dangerous to use due to a tendency to explode, early artillery was risky to its own side. In 1494, King Charles VIII of France tamed this dangerous beast, creating something remarkable.

Charles commissioned a force of uniform artillery. These guns of cast bronze were strong enough to withstand high-pressure powder charges, meaning that they could safely fire at a far greater power and range. They were also light enough to be easily transported to war. Against these guns, the previously invulnerable castle of Monte San Giovanni fell in only eight hours.

The Angle Bastion

Defensive technology had already been developed to counter guns such as Charles VIII’s and following his success it started to be widely used. This was the angle bastion.

First demonstrated in Tuscany by Giuliano da Sangallo, these defensive works were lower and thicker than those that had come before, with glancing surfaces and platforms for counter-bombardment. Often able to hold out against ever improving artillery, they provided successful defences until high explosive shells appeared in the 1880s.

Pavia

Artillery could be deadly, but it could also be vulnerable. At the Battle of Pavia (1525) French guns first devastated Habsburg troops, then were over-run by them as an ill-planned infantry manoeuvre blocked their field of fire. It was a lesson to all commanders – artillery on the battlefield must be deployed with care.

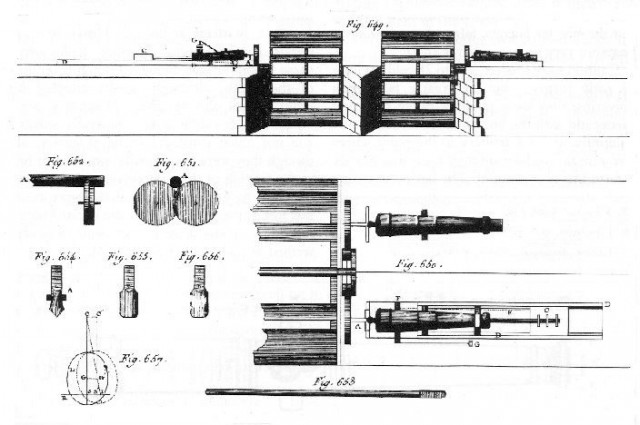

Jean Maritz’s Bored Barrels

In 1755, Swiss engineer Jean Maritz developed a new technique for boring barrels. By making the barrel and ball fit each other better, it allowed weaker charges to be used with equal power. This in turn allowed thinner barrels to be made, and so lighter guns.

French General Jean Gribeauval built upon Maritz’s innovation, developing lighter standard gun carriages. An artillery piece could now be hauled by six horses instead of a dozen or even more. Artillery had become more manoeuvrable.

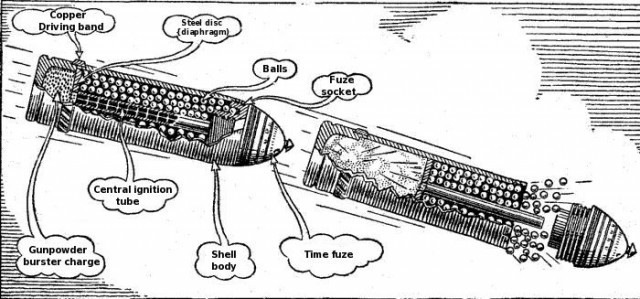

Shrapnel’s Fused Shell

Mortars had long fired exploding rounds, but it was not until 1784 that Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel brought the British Royal Artillery an innovation that would let cannon do the same. This fused shell would explode amid the enemy troops, showering them with deadly pieces of the casing – named shrapnel after the Lieutenant. First used in 1803 at Maida, it became even more deadly as gunners learned to time the fuses to explode above enemy heads.

Frederick the Great’s Horse Artillery

King Frederick II of Prussia (1740-1786) oversaw vast reforms in his nation’s armies. One of these was the formation of the first complete units of horse artillery. These batteries of light, mobile guns could be quickly moved around the battlefield, adding firepower wherever it was most needed. The success of Napoleon, history’s most famous artillery officer, was built in part upon adopting Frederick’s techniques.

Krupp’s Steel Guns

German industrialist Alfred Krupp is remembered for many artillery innovations, but perhaps the most important was the steel gun. Using this stronger metal, rifled to create a tighter, more powerful barrel, he surpassed anything achieved with the previous iron guns. By the 1870s, his barrels were made from a single flawless piece of steel, able to cope with fast advancing chemical explosives. Krupp’s innovations gave huge advantages to the Prussian and then German armies, before being adopted around the world.

The Soixante-Quinze

More powerful guns created their own problems. Larger carriages were needed to withstand the shock of recoil, leading to vast, unwieldy machines.

The solution was presented in the French soixante-quinze (seventy-five) gun, first demonstrated in 1897. By mounting the barrel on a piston, which was itself embedded in a hydraulic chamber, this gun allowed hydraulic fluid to absorb most of the recoil. Lighter gun carriages could once again be built, and time was saved rolling artillery back into place after recoils.

The Russo-Japanese War

The power of these innovations was demonstrated in the Russo-Japanese war (1904-1905). Using observers to direct their fire, Japanese howitzers destroyed the Russian fleet in Port Arthur. Field artillery loaded with shrapnel also devastated infantry on the battlefield, inflicting heavy casualties and driving survivors into cover.

It was a sign of things to come.

First World War

The First World War (1914-1918) saw artillery deployed on a scale and level of destruction never seen before. Entire landscapes were transformed as infantry took cover in trenches and bunkers, and entirely new artillery tactics were developed. Artillery became the dominant branch of all the armies fighting the war – by 1918 the British Royal Artillery had over half a million men, twice the size of the whole British army fielded in 1914.

Self-Propelled Artillery

Following the First World War, artillery diversified to fulfil different roles. Some pieces were still intended to attack infantry, but others became anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. It all remained cumbersome to move around, having to be dragged into place by other vehicles and adjusted by hand.

In the Second World War, self-propelled artillery – heavy guns on their own motorised carriages – brought in faster artillery support. In this way, the Russians advanced 400 guns into every mile of their line in the Battle of Berlin (1945).