By Jeremy P. Amick

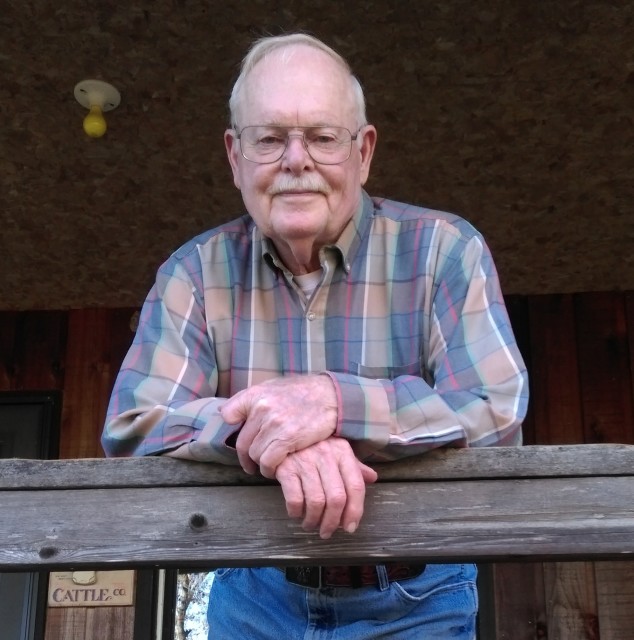

In his rustic home situated on 66 acres of woodland in rural Moniteau County, Mo., Richard Schroeder shared many chuckles while discussing the circumstances that led him into service with both the Navy and Marine Corps … more than sixty years earlier.

A 1950 graduate of Jefferson City High School, Schroeder explained that serving in the military was never his ambition while attending the Kansas City Art Institute.

“Back then, my future mother-in-law was the clerk for the draft board (in Jefferson City),” said Schroeder, 84, California. She said that if I was thinking of enlisting, I had better go ahead and do it.”

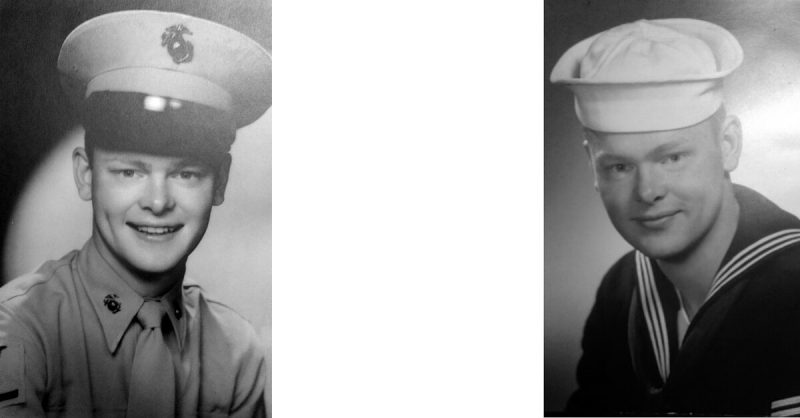

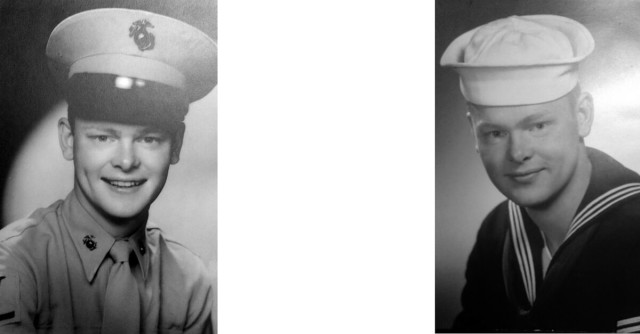

Schroeder and a friend decided to visit their local recruiting office to avoid being drafted. At first, they intended to enlist in the Marine Corps, but when the line for the Navy began moving faster, they decided to switch lines.

Enlisting in October 1951, Schroeder completed his boot camp at the Naval Training Center in San Diego with hopes of serving aboard submarines; instead, the Navy decided that his services could be utilized as a corpsman—enlisted medical specialists able to provide emergency care in a field environment.

“They sent me to Bainbridge (Maryland) Naval Training Center for hospital corpsman school,” said Schroeder. “I had no desire to be a corpsman because all I could think about was (patients) puking and all of that stuff,” he laughed. “So I tried to flunk out of the training by failing all of my tests.”

After months of training, the former sailor humorously noted, he graduated second from the bottom of his class.

Returning to Jefferson City on leave, he married his fiancée, Carole Schreen, in July 1952. He and his wife then returned to Bainbridge where Schroeder was assigned to an eye, ear, nose and throat clinic. Although he helped perform routine exams and assist with minor surgeries, one event demonstrated to him the dangers present with many forms of medical care.

“I was assisting a doctor with a bronchoscopy and the doctor sprayed the patient with Pontocaine (topical anesthetic),” Schroeder recalled. “The guy’s heart stopped and the doctor cut him open to massage his heart, but his hands were too big for the procedure. I had to stick my hands in and do it myself.”

Solemnly, he added, “The patient did not make it. That was a very traumatic experience for me.”

The young corpsman soon discovered all sailors were required to perform sea duty or complete a tour in an overseas location, resulting in orders attaching him to the Fleet Marine Force—a landing force comprised of U.S. Marines and supported by elements of the Navy, including corpsman.

“I spent some time in training at Camp Pendleton (California) and attended what was basically a shortened Marine boot camp,” he said. “Then I took field medical training, learning to deal with trauma injuries such as shock, head injuries and amputations. Also,” he continued, “we were issued Marine uniforms.”

He became a member of the Third Marine Division and traveled by troopship to Japan. Following his two-week journey across the ocean, Schroeder, as part of “Easy” (E) Medical Company, was attached to a headquarters unit stationed in an outpost near Nara, Japan; which, he described, was “in the middle of nowhere and surrounded by rice paddies.”

During the next year, he applied his medical training in a quite unexpected fashion.

“The job I was assigned was venereal disease (VD),” he soberly remarked. “The (Marines) would come in with an issue and I would have to take a sample to be tested to determine if a VD or something else was causing their problems.”

His duties, he noted, also required him to accompany a Japanese doctor and three Japanese police officers on weekly visits to local “establishments” to determine where the men were acquiring their ailments.

“In Japan, prostitution was legal and the government was very good at keeping everything clean,” he said. “Each prostitute was given a government card with a number on it and each month they had to have a physical exam.”

Also participating in regular military training maneuvers as a medic supporting amphibious landings and battle simulations, Schroeder completed his overseas tour in the summer of 1954, returning to the United States to reunite with his wife and meet his 9-month-old son.

Schroeder completed his enlistment at a clinic on New Orleans Naval Station, receiving his discharge in September 1954. He then moved his family to Columbia where he enrolled in the University of Missouri, using his GI Bill benefits to earn his bachelor’s degree in education.

In the years following his discharge, his family grew in size to three sons and a daughter. He was hired as an agent with the Missouri Department of Conservation in 1960 and went on to retire from the agency with 30 years of service.

Reflecting on his brief military career—one with many interesting and unexpected deviations—Schroeder said that he has since benefitted from the training he received, albeit in a specialty he initially viewed as objectionable.

“Although I first wanted to serve on submarines, because of the education that I received in first aid and healthcare, I was able to get a job while in college at the MU Medical Center—that really helped me support my family,” he said. Had I been in the submarines, I would never have earned these skills,” he added.

“But, looking back,” he paused, “the best part of it all was the way it helped me grow up—I got away from my parents and all of those who regulated my activities as a young person and learned to make my own decisions.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Jeremy P. Ämick

Public Affairs Officer

Silver Star Families of America

www.silverstarfamilies.org