War History Online presents this Guest Article from by James Stejskal

Think the Russian threat worries the United States now? At the height of the Cold War, the US military planned to stop a Soviet attack by any means. This is how one small group of men would have done their part.

West Berlin, March 1957

An American, who we will call “Thomas,” steps outside a cafe into the frigid air. He just finished a quick meeting with a German man to discuss some details on an apartment he wants to rent. The two men shake hands and part ways. Thomas returns to his office after following a circuitous route that shows he is not being followed. He appears to be just another face in the crowd.

The German knows him by another name. Thomas is in civilian clothing and speaks German very well. The owner thinks he comes from another country altogether, not the United States. Thomas is a U.S. Army Special Forces soldier – a “Green Beret” – stationed in Berlin and he just rented a “safehouse” for his team’s operations.

Thomas is part of a classified U.S. Army Special Forces (SF) Detachment in West Berlin, 110 kilometers deep inside Soviet-occupied East Germany. His cover unit is innocuously named Detachment “A” Berlin Brigade, or “Det A” for short.

Thomas’s job and that of the other 89 men like him is simple: prepare for war against the one million men of the Soviet and Warsaw Pact armies lurking several kilometers away. The mission was simple, if war came, the men of SF Berlin would exfiltrate the city into the rear areas of the Soviet forces. Once there, they would cause havoc by blowing up bridges, fuel dumps, and attacking key command and control facilities. It was a desperate – some would say a suicidal – mission. Especially if they were captured in civilian clothing or an enemy uniform behind the lines. But, from 1956 to 1990, six Special Forces “A-Teams,” were ready and able to do just that. Each team a specific area of responsibility and they trained intensely for the mission.

In the late 1950s, when the prospect of another war seemed very real, nuclear weapons were America’s chosen means to slow a Soviet attack. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) estimated that 92 Warsaw Pact divisions would come pouring off the steppes of Russia into Western Europe would quickly overwhelm the West unless desperate measures were taken. Nuclear weapons were the solution to that problem.

Nuclear bombs, missiles, and artillery projectiles were high on the list of President Dwight Eisenhower’s “New Look” strategy of deterrence. Less well known among these were the devices called “atomic demolitions munitions.” These were small nukes, relatively speaking, with a yield in the low kilotons, originally designed to be used by combat engineers to mine routes and destroy bridges in front of the approaching enemy. But then someone in the Pentagon came up with what they undoubtedly thought was a bright idea: “We can stop an invasion by dropping US Special Forces teams armed with nukes into Eastern Europe and letting them wreak havoc in the Russian backyard.” This mission was so classified in the United States that they only admitted its existence in 2014.

Special Forces received this mission in 1956 and began discussing possible ways to get the devices to a target. At first, SF worked with ADMs that were much bigger than the later Special Atomic Demolitions Munitions (SADM), the so-called “trashcan” or “suitcase” nukes. The ADM-4 was the first such “man-portable” weapon adapted for the task. Its yield was in the “low kilotons” – small in size compared to the big weapons on board a B-52 or a Poseidon missile. It was too large and heavy to be carried by one or two men, but a well-trained team could. It was a standard nuclear weapon redesigned to be broken down into four major components, each piece weighed between 40-50 pounds. The complete device weighed around 200 pounds.

No plan, concept, or theory in the military can be accepted without it first being tested and who better to be the guinea pigs but the men who would carry it onto the battlefield?

When Thomas got back to the unit headquarters, he found his Team Five had been tasked to conduct a test of the Top Secret nuclear sabotage mission.

One team member later said that “being on the mission was a challenge. Security restrictions meant that no one could discuss any aspect of the operation.” The unit’s other teams were not told of the mission. Team Five spent several weeks at a location in West Germany training up on the ADM-4 and then prepared to conduct a practice exercise.

The mission was to destroy a simulated aircraft factory in southwestern Germany, a location chosen because of its similarity to sites in the Eastern Bloc. The ten-man team would be joined by two evaluators from the 10th Special Forces Group in Bad Tölz. To ensure the security of the device, the “enemy” would be played by American soldiers. No one wanted a foreigner to discover the device and its purpose.

After completing the training and planning, Team Five jumped into a small open field somewhere in the Black Forest. They moved slowly to a camp set up by their advance team, two men who had jumped in earlier. Two men moved forward to a forward observation post and watched over the target through the next day. The team leader’s reconnaissance determined the final plan.

The advantage of the nuclear device was clear; its placement did not have to be precise, it needed only to be reasonably close to the target. Half the team would approach the target the following evening while the other half provided security to their rear. In the real world, the team could not be captured. If necessary, the device could be assembled and fired. The team understood that if they were detected they would not be going home.

The following evening, the attacking team moved into position undiscovered by sentries and assembled the weapon about 100 yards from the target buildings.

Assuming the timer worked as advertised and not instantaneously as some skeptics surmised, they would have an hour to exit the area and get as far away and under as much cover as possible before the weapon went off. Pushing the fire button, the timer started and the team backed out of the area carefully. They joined up with the other half of the team and started to move away.At this

At this point, the victory was declared and the exercise ended. The observers determined that all the required steps had been done correctly. The team dismantled the device so it could be returned to a secure bunker somewhere in Germany and then, relieved both figuratively and literally of their burden, the team returned to Bad Tölz for a shower and a trip into town for some Bavarian Gemütlichkeit – a schnitzel, beer, and whatever the night would bring. It was back to Berlin next morning. The SADM mission was validated.

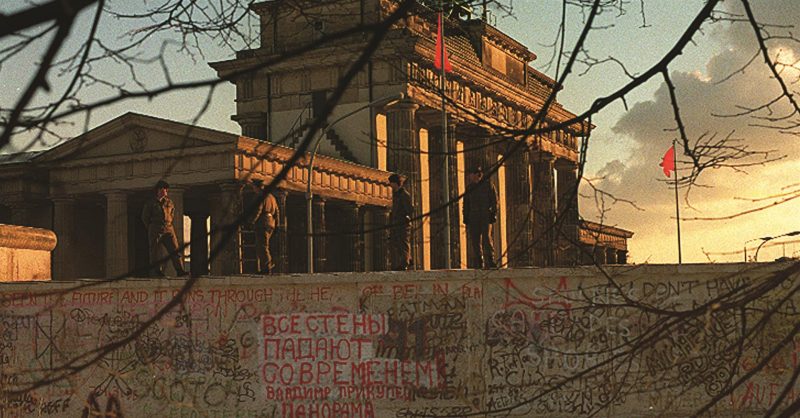

The men of Special Forces Berlin served in the “Outpost of Freedom” until 1990, leaving the city only after the Iron Curtain fell. They took part in many classified missions in Europe and elsewhere until, with the dividends of “peace,” the unit was inactivated. The men were sent elsewhere to continue their job of defending the United States and their allies.

This article is from an upcoming book: Special Forces Berlin: Clandestine Cold War Operations of the US Army’s Elite, 1956-1990 (Casemate US/UK, Feb 2017) by James Stejskal.

All photos are provided by the author.