The submarines of the United States Civil War were not the first to appear on the sea. The successful use of submersibles dates to Alexander the Great, and the first submarine design dates to 1578.

For the next few hundred years, many designers built submarines, but for one reason or another, they either failed or lost funding.

The first submarine to sink an enemy ship was built during the Civil War. Both the Union and Confederacy built submarines that had successful trials and worked as underwater vessels.

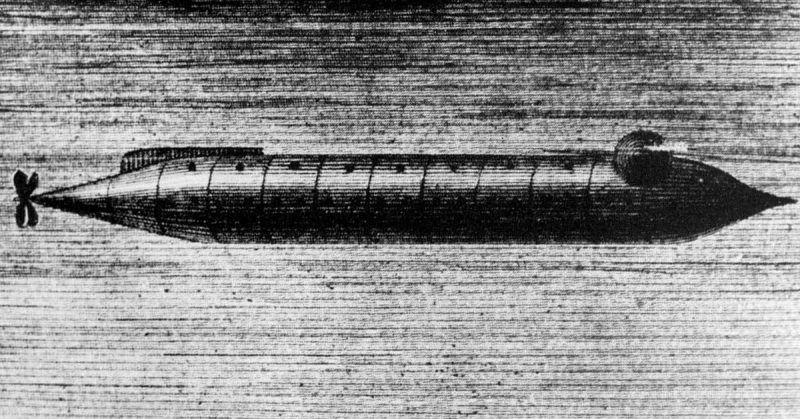

USS Alligator

The aptly named Alligator was the first submarine in the United States Navy. She was sleek, made of iron, and was the very first submarine to have both an air purifying system and a lock that allowed a diver to exit while under water.

The vessel’s military mission was to ferry a diver close enough to enemy ships that he could plant explosives on their hulls and make a getaway before they exploded.

Unfortunately, the Alligator never got her chance. On the way to Charleston Harbor, she was lost off Cape Hatteras in a storm. The Navy, the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Association, and the Office of Naval Research are all still actively looking for the lost submarine.

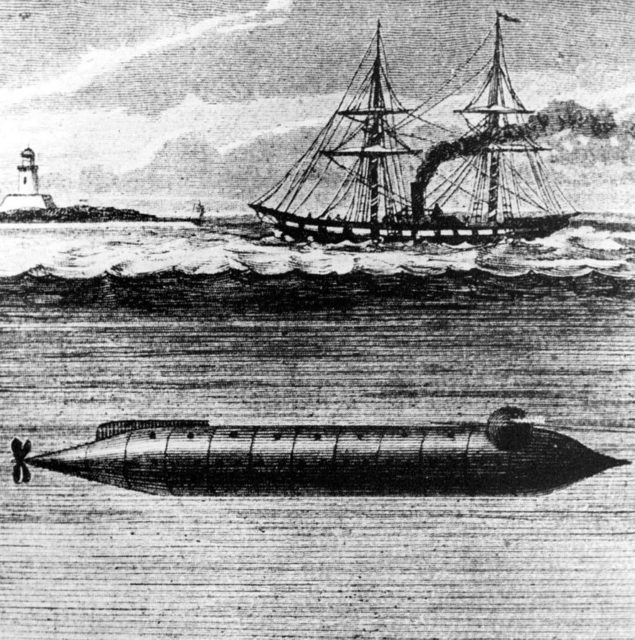

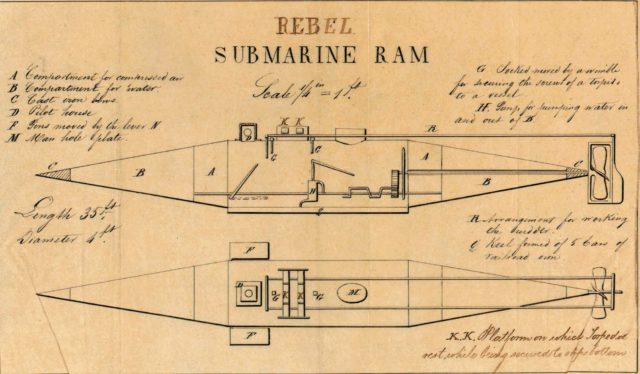

Pioneer

Horace Lawson Hunley’s first attempt at building a submarine was the Pioneer, built in 1862. He and fellow developers Baxter Watson and James McClintock were responding to Jefferson Davis’s, call for privateers to help resist Union blockades of Southern ports.

The Pioneer, as described by McClintock, was “made of iron ¼ inch thick . . . was of a cigar shape 30 feet long and 4 feet in diameter. . . we were unable to see objects passing under the water; the boat was steered by compass…” The sub worked with a crew of three men, two of them hand-cranking the propeller.

When the Union brought down New Orleans – near where the trio was testing their submarine – the inventors decided to scuttle her in the New Basin Canal. They were too late. The Union had already heard about the project and soon brought the Pioneer back up to check her out and report back with detailed diagrams of the vessel.

American Diver

Hunley, McClintock, and Watson moved their engineering operations to Mobile, AL to try again. This time, they attempted electric motors and a steam engine but had to return to the hand crank method. This version, also called the Pioneer II, added two extra men so there were four hand cranking and a fifth to steer.

They tried to run her against a Union blockade in Mobile Bay, but she was too slow. She later sank, with no crew aboard, and remains somewhere at the bay entrance today, undiscovered.

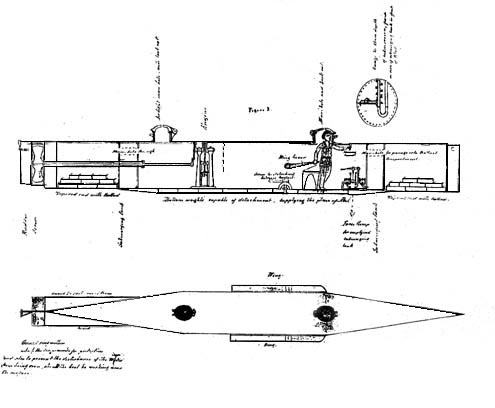

Hunley

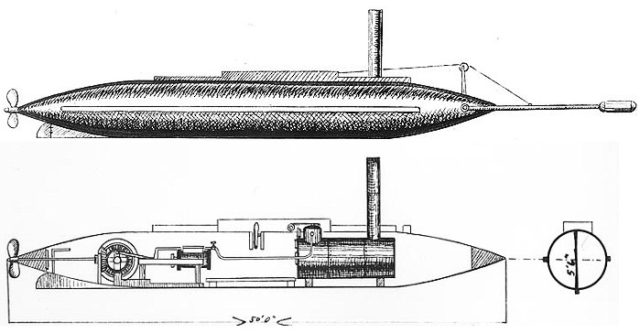

Though dubbed the “world’s first successful submarine,” the Hunley was the first military submarine in the world to successfully complete an offensive mission. She sank the USS Housatonic five miles off shore near Charleston harbor.

The Hunley was designed by the Hunley/McClintock/Watson group but was seized by the Confederates for use in their Navy. Hunley stayed on to supervise further testing but was drowned when a mock attack went wrong.

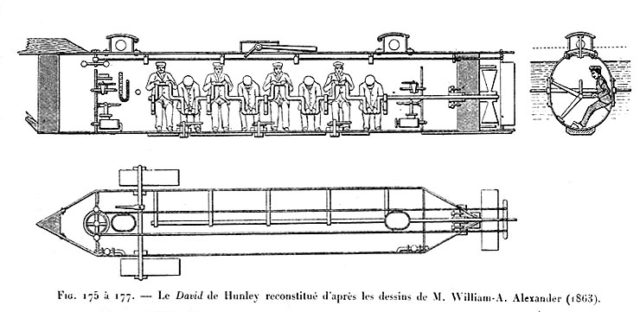

The submarine’s purpose was to fire torpedos. She was hand cracked by a row of eight seated men along the length of the vessel and steered by a ninth.

A spar torpedo was mounted to the bow by a long ramming pole. The explosive charge was equipped with a trigger that worked much like a flintlock on a rifle. The trigger was linked to the hull of the Hunley by a very long rope.

When the Hunley rammed the torpedo into the underside of the Housatonic and backed away, the trigger engaged and the torpedo exploded like a giant underwater gun.

The Hunley was successful in sinking the Housatonic, but she did not survive the attack either. Researchers have considered that a piece of copper at the end of Hunley’s spar indicates that she was only 20 feet away when the torpedo exploded and this may have knocked the crew unconscious and they subsequently died from lack of oxygen.

CSS David

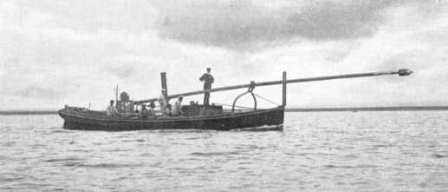

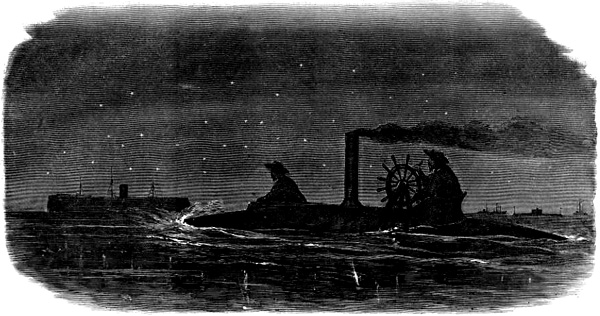

The CSS David was not technically a submarine, but she looked like one and was nearly as invisible.

The vessel was a semi-submersible torpedo boat, the one on which the successful weapon mechanism on the CSS Hunley was based. She was 50 feet long, and only the boiler stack and periscope tower could be seen above water when the ballast tanks were filled with water.

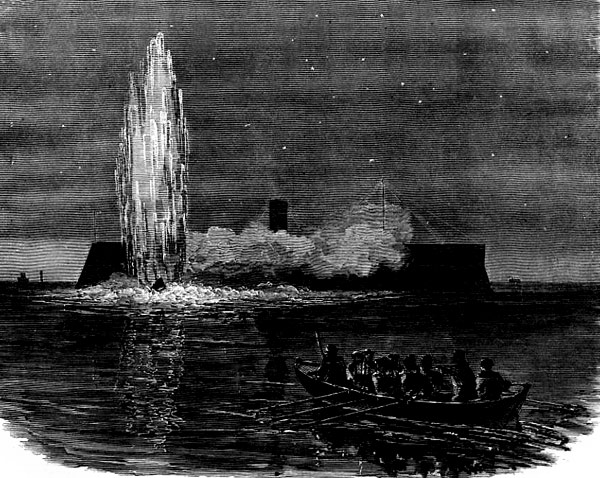

The David was successful in its first attack. One night in October 1863, she approached the USS New Ironsides. The captain of the New Ironsides saw the David and fired at her with a shotgun but missed. The David plunged ahead and hit Ironsides at bottom starboard.

Even though the detonation sent up only a column of water which put out the boilers, the New Ironsides captain ordered his crew to abandon ship.

Due to the success of the CSS David, the Confederacy ordered more torpedo boats – as many as twenty. Most were seized by the Union when Charleston was captured, so the fate of the David is unknown.

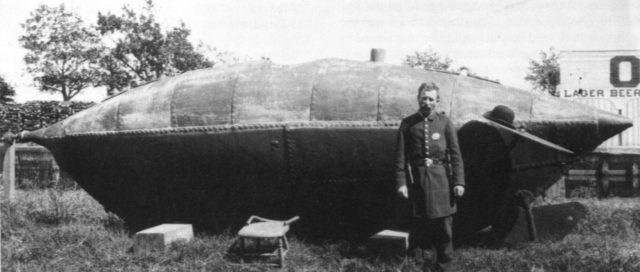

Bayou St. John

This submarine is a mystery to historians. There is no known period documentation of the craft.

It was pulled out of the Bayou St. John in 1878, and for years was thought to be the Pioneer until a historian noted the dimensions were not the same. The Bayou St. John is 20 feet long, while the Pioneer was 30 feet long. There is also the fact that the Union brought the Pioneer back to the surface shortly after she was scuttled to gain insight into Confederate naval plans.

It is believed that she was scuttled around the same time and for the same reasons as the Pioneer – to hide her from the Union troops that had taken New Orleans.

Historians continue to try to identify her, but no luck yet.