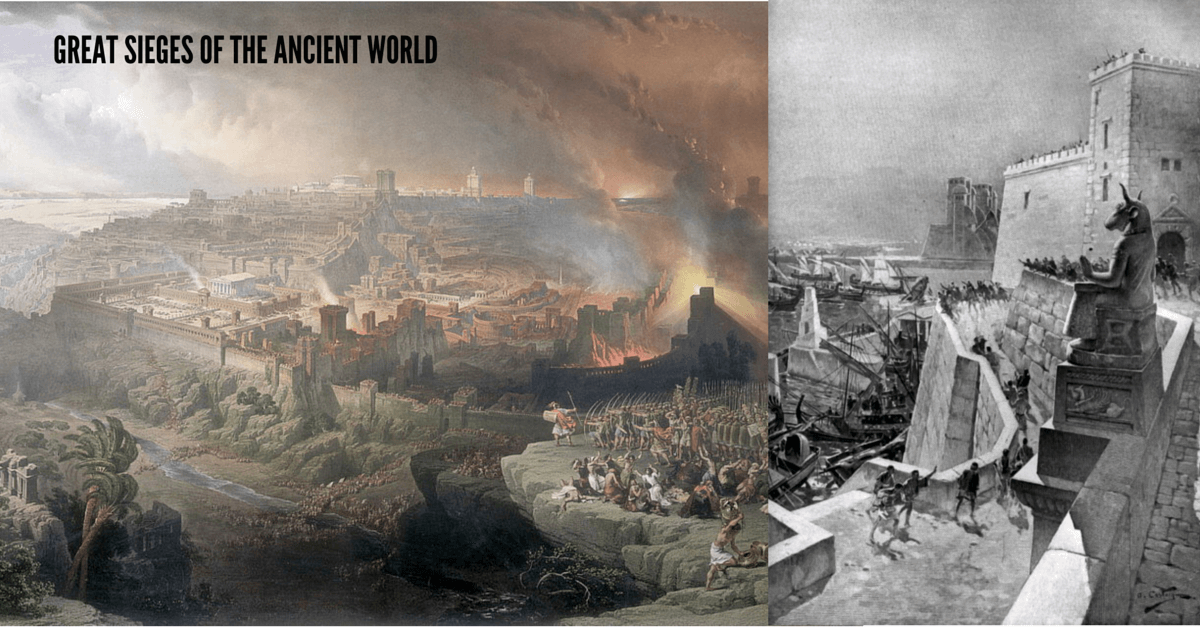

a painting by David Roberts (1796-1849).

‘Great battles’ is a popular theme for military historians and an important one to discuss; as war is often a driving factor for historical change, great and decisive battles are the essence of those wars. Too often the great sieges get left out, despite their equal or even greater importance to the outcome of wars. This series of articles will profile some of the greatest sieges of the ancient world, from the Siege of Megiddo to the sack of Rome. Though ‘siege’ is implied as the waiting outside of the city, assaults will also be covered in this series. For those who are unfamiliar there are a few basics to know about ancient siege warfare.

A walled city was one of the most effective forms of protection for many millennia. A sturdy wall gave cities great views of approaching enemies and the advantage of elevation for missile attacks. Even when scaled or breached, walls still gave the defenders an advantage by constantly bottlenecking an assaulting force. Despite the impressive fortifications erected in the Ancient world, many still fell to besiegers. There were several ways a siege could end; capture or sack, the besieged army surrendering, the besieging army giving up, or the besieged army marching out/ sallying forth for a field battle.

Sacking a city through an assault was the most difficult but most decisive result for an attacking general. The first order was to get through or over the wall. This involved siege engines which ranged from ladders or covered wheeled towers to scale the wall, battering rams to go through the gates, or tunneling under or firing catapults to collapse a wall. Additionally, assaults could be started by a traitor on the inside who could open the gates, or by way of a secret entrance such as the shallow lagoon assault at the siege of New Carthage.

When a besieged city surrendered, it was often after months or years of siege. Depending on the city, it could have access to the sea as Athens did with its long walls reaching to the port, or it could have a huge cistern like that in Constantinople. Even when completely surrounded it could take years before a city was starved into submission. If a city held out long enough it could make the attacking army run out of supplies or simply lose the will to keep up the siege.

Lastly, though there are other unique ways sieges ended, another common method was a decisive battle outside the walls as the besieged force attempted to force a fight. This is seen at the sieges of Alesia and Numantia. Such a fight usually forced an outcome, and it was often a desperation attack by the defenders.

Sieges were often defining moments in ancient military campaigns. They secured a population center and the region it controlled, including any port facilities and treasuries. In ancient Greece sieges had a special weight as the individual cities held all the power. Several sieges will be covered with emphasis on what made them ‘great sieges’, if you have any you think should be covered feel free to leave a comment.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online