In the early 1800s, two US generals tried to invade Canada. They might have succeeded, too, except for a peculiar handicap – their inability to tell friend from foe.

Officially, America broke free of the British Empire on July 4, 1776. The truth, however, was a lot more complicated.

Britain still ruled the waves (and Canada), so they put trade and maritime restrictions on the new republic. They also kidnapped thousands of Americans, forcing them to work for the Royal Navy because they viewed them as British subjects – a practice known as “impressment.”

Finally, they tried to limit America’s expansion by supporting Amerindian tribes. Britain even planned to set up an Amerindian buffer state in the Midwest to stop American settlers from moving there.

Things came to a head during the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815). Conscription in Europe reached ridiculous levels, and America was not immune as more of its citizens were press-ganged into Britain’s navy.

Then Napoleon embargoed Britain, so they retaliated by doing the same to France. As a neutral country, America had no qualms about trading with anyone – including the French.

This upset Britain, of course, so they blockaded American ports. It did not last. America’s resources were too valuable, so the embargo ended in 1809. Not so with impressment.

Enough was enough! On June 18, 1812, President James Madison signed America’s first declaration of war – not knowing that Britain would ban impressment ten days later (though not because of him). The war was not necessary, but it took a while for news to cross the Atlantic.

Thus was the beginning of the 1812 War (which went on until 1815). The timing could not have been worse. Britain was fighting France, so did not have enough resources to protect Canada.

America was no better off. They had an army of barely 12,000 men – most of whom were inexperienced. Worse, there was as yet no concept of an American identity. Each territory had its own militia, loyal to their state, alone; not to some greater America, as a whole.

Even worse, the US had disbanded its national bank. That left private banks who were opposed to war – a sentiment shared by some states who threatened to secede.

Despite this, General William Hull crossed the Detroit River on July 12, 1812, with about 1,000 ill-equipped, poorly trained, and poorly paid American soldiers. By the end of the day, they had taken Sandwich – a Canadian town (now a suburb of Windsor, Ontario). By August, they had been pushed back across the Detroit – a precursor of things to come.

Fast forward to 1813. The US-Canadian border was in constant flux as British, Canadian-British, pro-British Amerindians, and Americans fought back and forth across it.

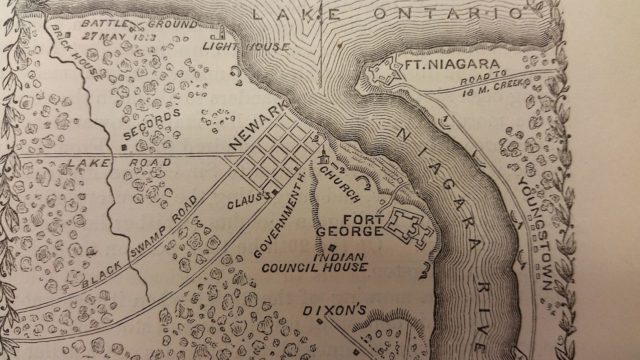

Along Lake Ontario were the Americans at Fort Niagara and the British at Fort George. On May 25, the US Army and Navy attacked – taking Fort George two days later and forcing the British to flee.

Brigadier General John Vincent felt sure the Americans would give chase. Needing speed, he disbanded the militia, ordered them to scatter and fled to Burlington Heights in Ontario with about 1,600 regulars.

But the Americans were not in a hurry because they were under General Henry Dearborn. Though an experienced military man, he was also 62 and was not feeling too well.

General William Henry Winder was therefore tasked with chasing Vincent. Winder did so until he reached Forty Mile Creek. A thoughtful man, he concluded the British far outnumbered his men – so decided to stay put.

He was still doing just that when Brigadier General John Chandler and his brigade came along. As together they now numbered some 3,400 men, Chandler ordered the chase to continue. They reached Stoney Creek on June 5 and made camp at the Gage Farm (now Gage Avenue in Hamilton, Ontario).

Vincent was not too far off, however, so he sent Lieutenant Colonel John Harvey to scope out the enemy. Harvey’s assessment was mixed. Yes, the Americans far outnumbered them. But! They were too spread out, their guards were too few, and they had too many vulnerable spots.

Conclusion? Attack their front at night. Vincent liked it, so he put Harvey in charge of the assault. At 11:30 PM, the British left Burlington Heights and crept silently toward the Americans.

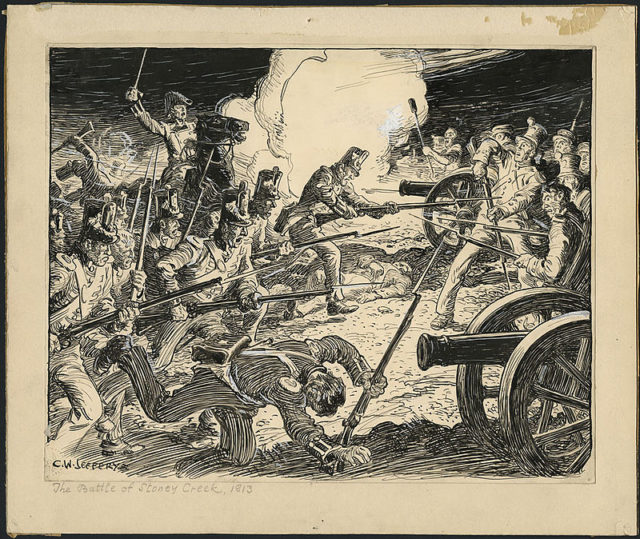

They killed the sentries and made their way toward the camp, ready to attack the US 25th Regiment. But the regiment had been moved to a more secure position, leaving only the camp cooks.

In the excitement, some of the British soldiers could not help cheering which told the Americans exactly where they were. Those at the center fired back, but Harvey had been right – they were too thinly spread out.

Chandler, who was too far off, heard the shots. He rushed to the scene, still wondering what was happening when his horse was shot out from under him (or slipped, depending on whom he later told the story to), and he passed out.

Major Charles Plenderleath, the commander of the British 49th Regiment, wanted the American field guns. He ordered a suicidal charge, just as the US 2nd Artillery stopped firing their cannons for reasons still in dispute. The 49th slaughtered them, then attacked the US 23rd Infantry, which fled.

That was when Chandler finally came to, “Thank goodness, you’re all here! The British are attacking! Hold your positions, men!”

Though it took him a while to notice their accents, it did not take the 49th long to take him prisoner. Which left only General Winder.

He was also too far off. To remedy that, he rushed to the center and straight into the 49th – becoming their next prisoner.

Cavalry officer Colonel James Burn then took charge of the Americans. He ordered a counter-attack and with a mighty roar, his men charged and fired…

At the US 16th Cavalry who, in the darkness and confusion, were also shooting at each other. Faced with such a massive “enemy,” the Americans retreated – not realizing that they still outnumbered the British (who were probably scratching their heads).

It was over in 45 minutes. Harvey did not want the Americans to know just how few his men were, so he ordered a retreat. British losses were enormous, but they did get two American field guns and ruined a few more.

The Americans never crossed the Niagara after that – ensuring the integrity of the US-Canadian border.